Learn CUTLASS the hard way - part 2!

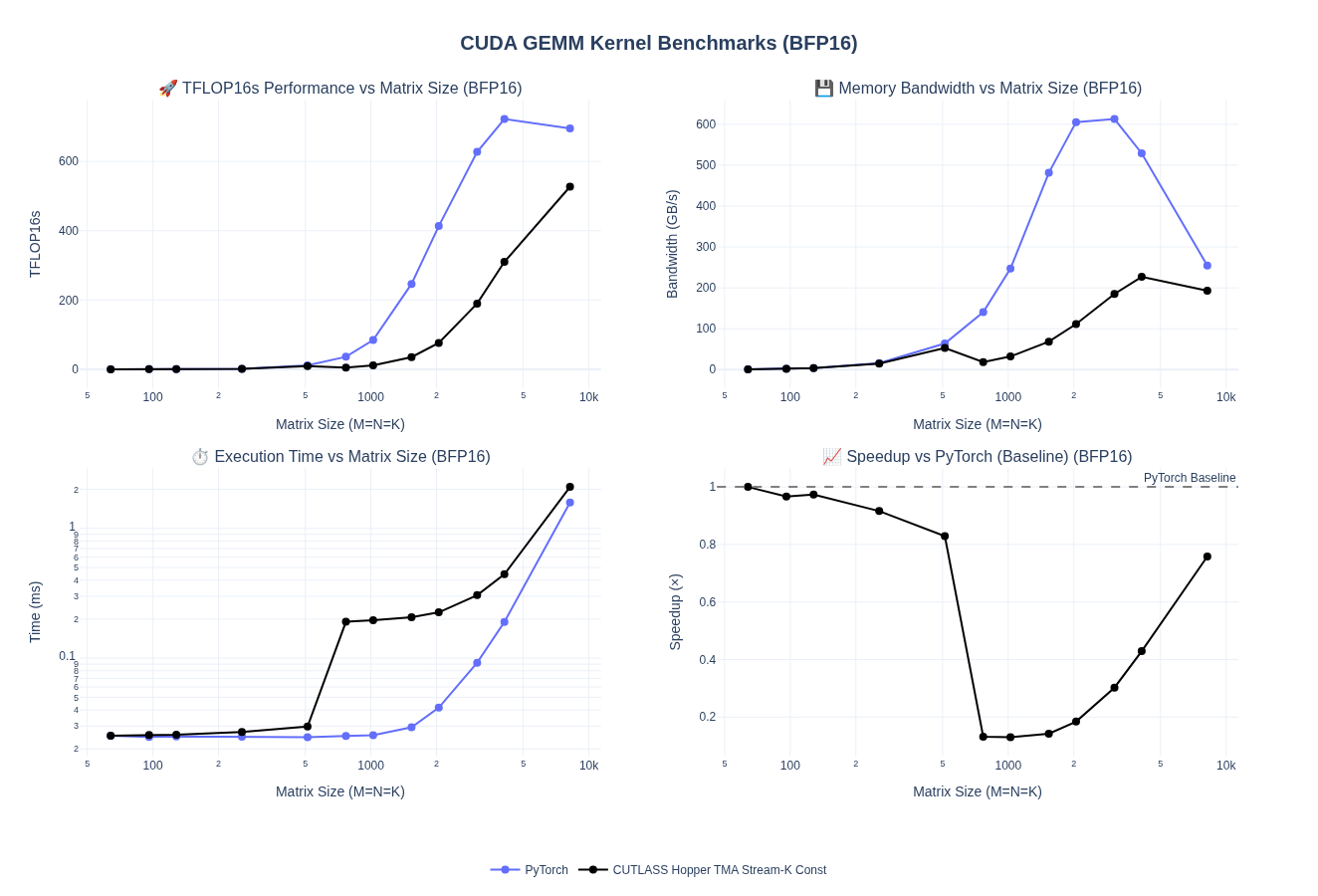

Exploring Hopper Architecture on H100 and try to match PyTorch/cuBLAS performance for GEMMs using CUTLASS

This is a continuation to my previous post Learn CUTLASS the Hard Way and here I will explore Hopper architecture. There were several new architectural changes that made it to H100 and had huge implications on the performance of GEMM kernels, specially for 16-bit and lower precision GEMMS. There is already a great post from Pranjal on his H100 Journey at Outperforming cuBLAS on H100: a Worklog. Expect this post to be a bit more higher level than that as I will primarily use CUTLASS to leverage the same optimizations.

Setup

For experimentation and testing the kernel performance on H100, I used Verda GPUs mostly. I was able to get spot instances most of the time with $1/hr pricing.

Javascript visualizations below were created with the help of Claude Code.

All the code is in the same repo as before in part 1.

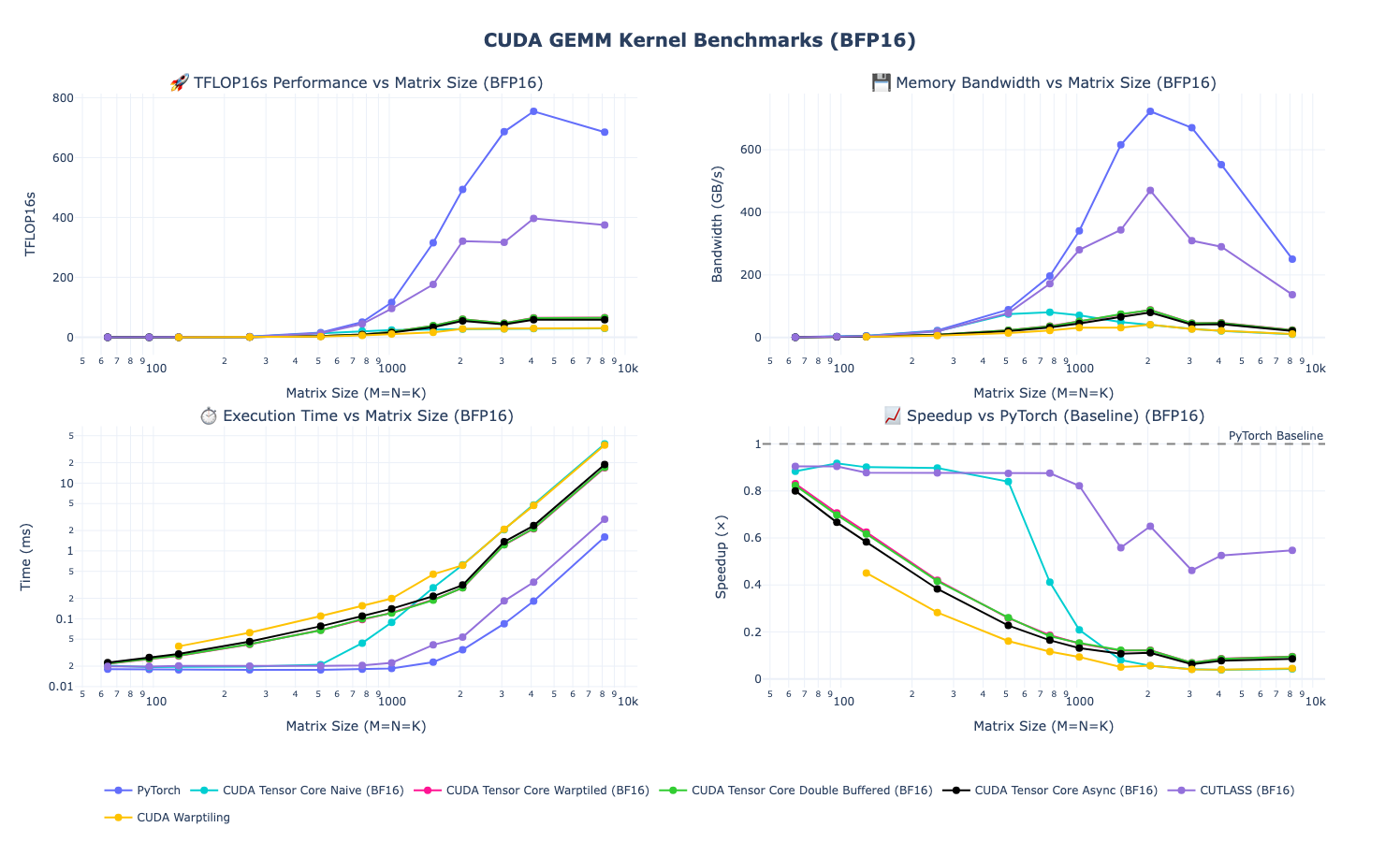

My Previous Baseline

Before we jump into Hopper kernels, let’s start with baselining the kernel we wrote for Ada (RTX 4090) on H100. We already had a CUTLASS kernel that we wrote in the previous post. It leveraged CUTLASS 2.x API and was primarily meant for Ada and older generation of GPUs. But, we can still run it on H100 to get a baseline performance.

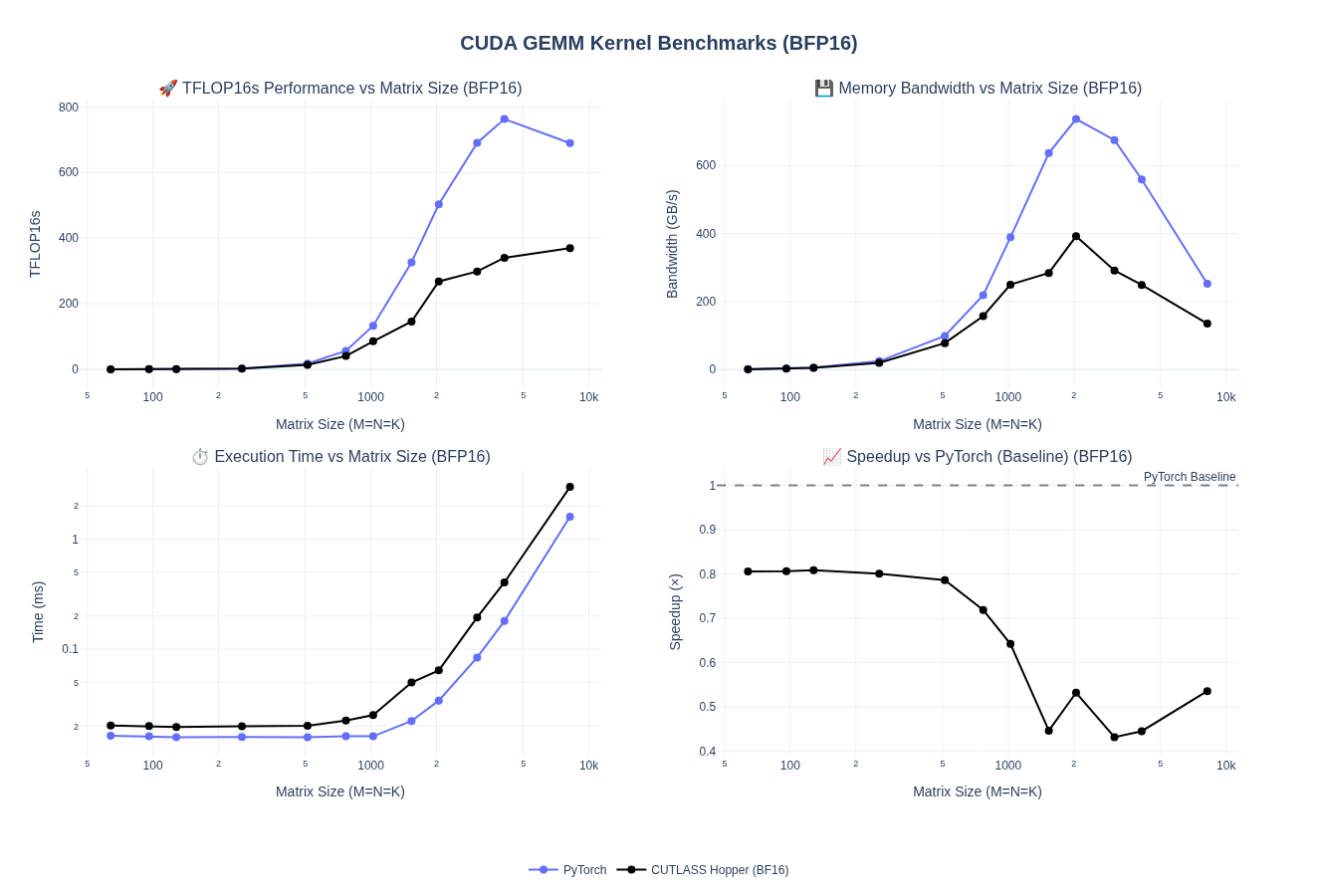

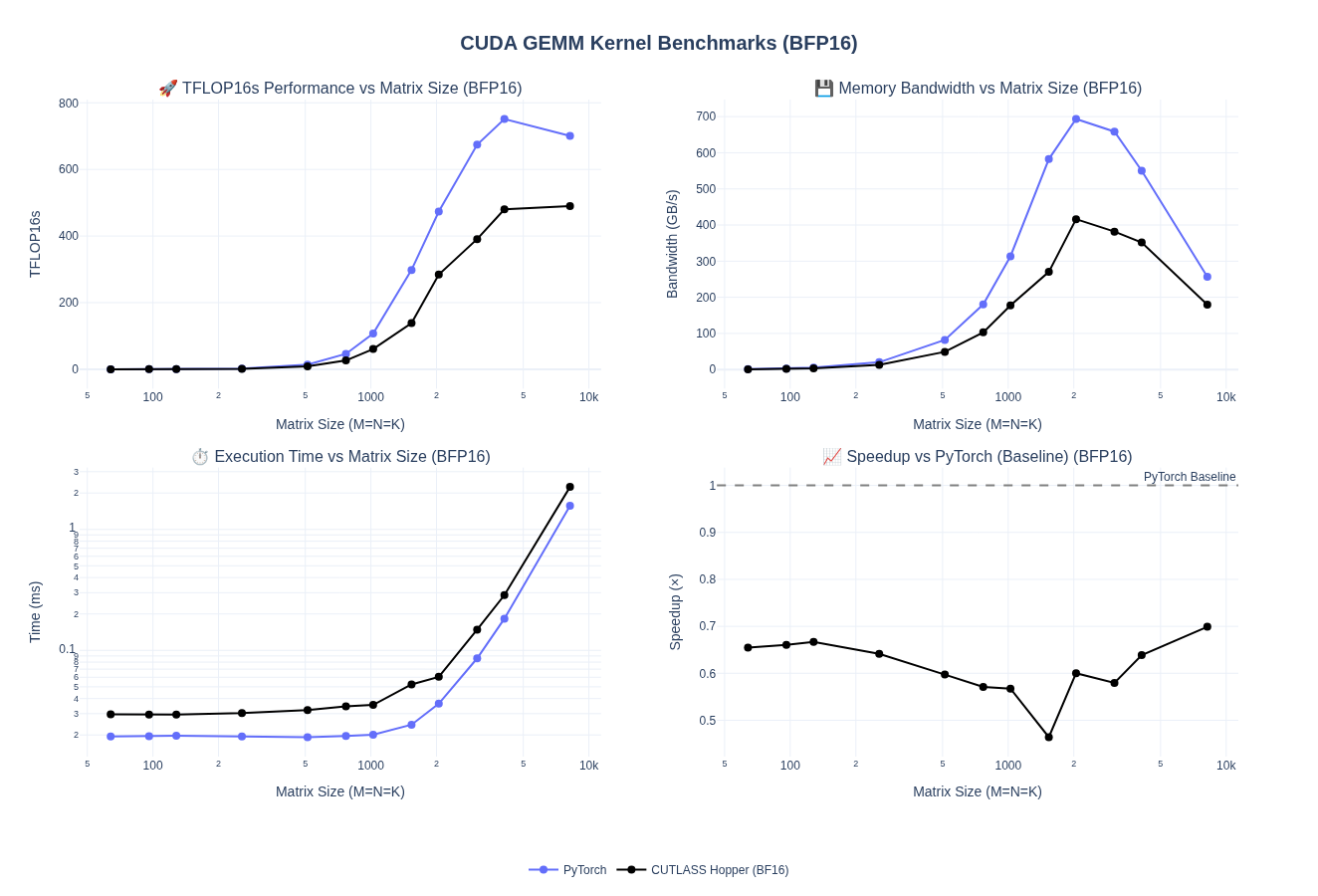

Baseline Performance of kernel_cutlass

- Small matrices: Both implementations are memory-bound at smaller sizes.

- Medium matrices: Performance diverges significantly and we can see our kernel isn’t leveraging H100’s architectural improvements and peaks out at slighly over 300 TFLOPs

- Large matrices: The gap widens further as my previous kernels peak out at ~400 TFLOPs while PyTorch continues scaling until we hit compute boundness

The performance cliff at medium-to-large matrix sizes reveals that our Ada-optimized kernel leaves significant H100 compute on the table. The hand-written non-CUTLASS implementations perform even worse.

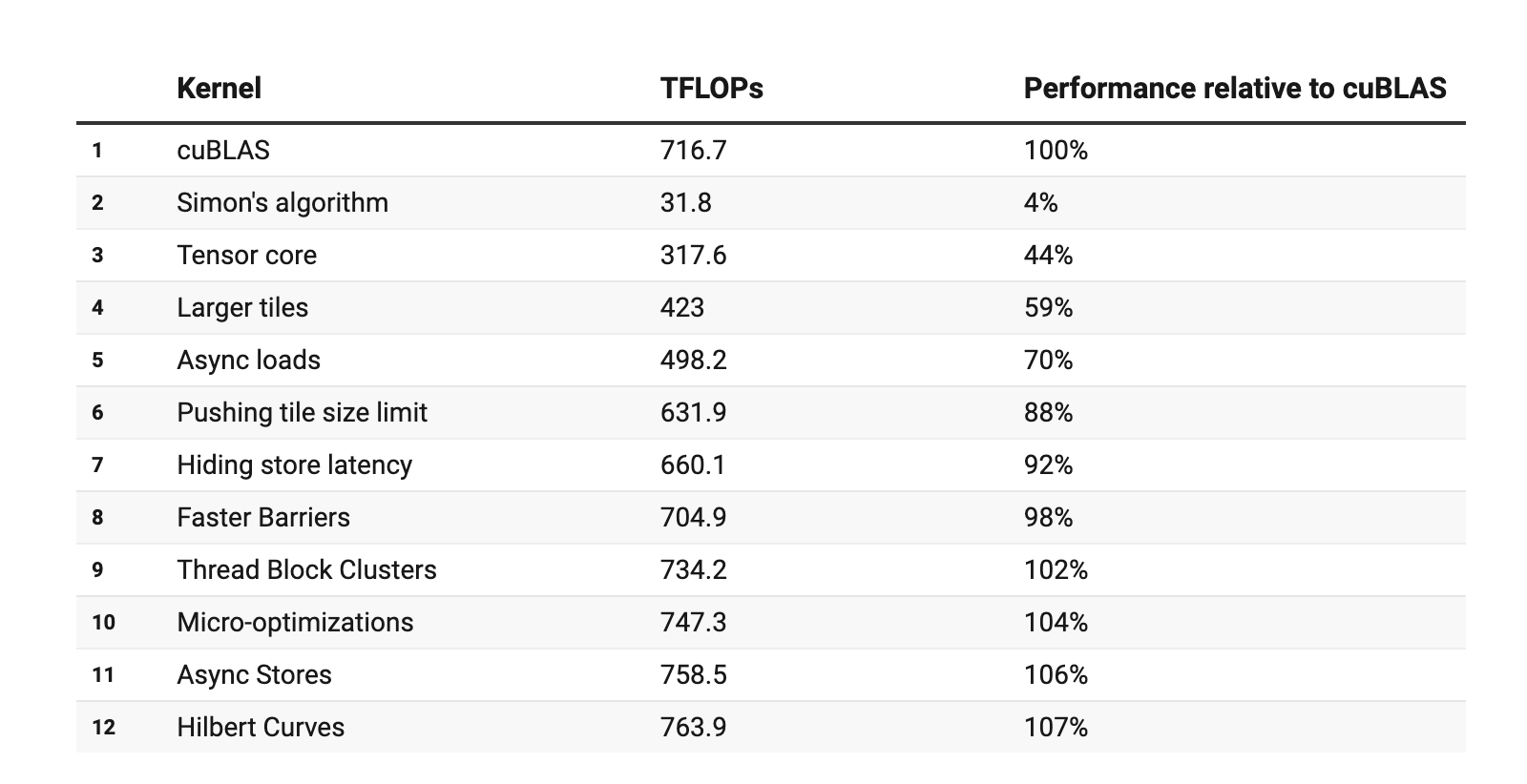

Autotuned Results

Let’s run our original autotuned kernel now, which hopefully should perform slightly better:

It seems surprizing to me but autotuning successfully extracts ~2x performance for small GEMMs but I am assuming it is just better register use for smaller sized kernels compared to PyTorch version, which I expect to be more generic. However, it is pretty visible that the Ada-optimized kernel implementation can’t exploit H100’s full potential at larger sizes, as was also shown in Pranjal’s Post on H100 post. Looking at his results the perf for our performance here for larger sizes falls somewhere in the region of “Larger Tiles”

Key Changes in Hopper

Without making it sound like an NVIDIA marketing presentation, I will try to cover some of Hopper’s architectural features that matter most for GEMMs in the coming sections and then we will look at some kernels.

Thread Block Clusters

Hopper added a new hierarchy level above thread blocks called Thread Block Clusters (TBC), groups of up to 8 thread blocks that can cooperate. This includes a distributed shared memory such that thread blocks in a cluster can directly access each other’s shared memory. This allows for better data reuse across blocks without going through global memory. As a result, new programming pattern has emerged where we need to partition work across TBCs rather than just within block. Overall, TBCs boost performance by enabling cooperation across multiple SMs, giving kernels access to more threads and a larger effective shared-memory pool than a single thread block can provide.

Source: NVIDIA Hopper Architecture in Depth

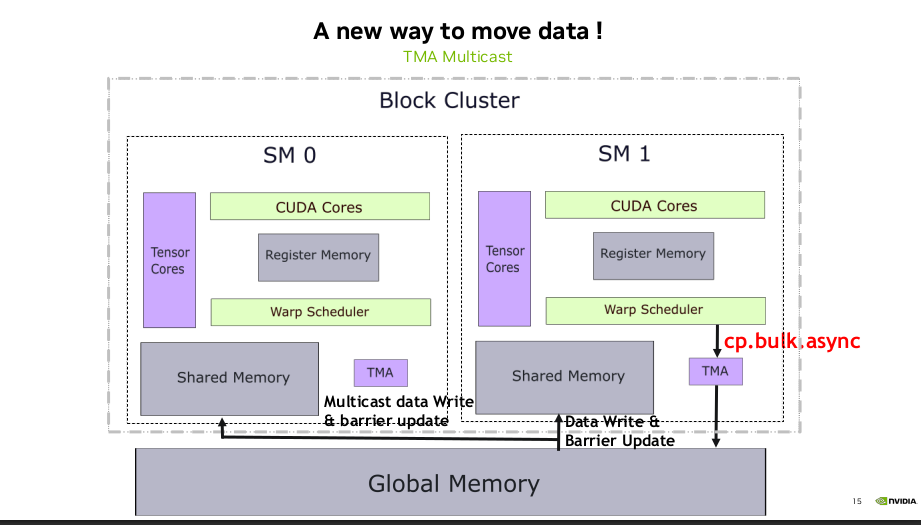

Tensor Memory Accelerator

Tensor Memory Accelerator (TMA) is arguably one of the biggest architectural change in Hopper. TMA is effectively a new way to move tensors from/to global memory to / from shared memory, while avoiding extra roundtrips of going through register file and instead writes / reads shared memory directly. In addition, data can be multi-casted to threadblocks in a cluster (see above for TBC). There are other features such as automatic bounds-checking, zero-out, etc that also help reduce overhead.

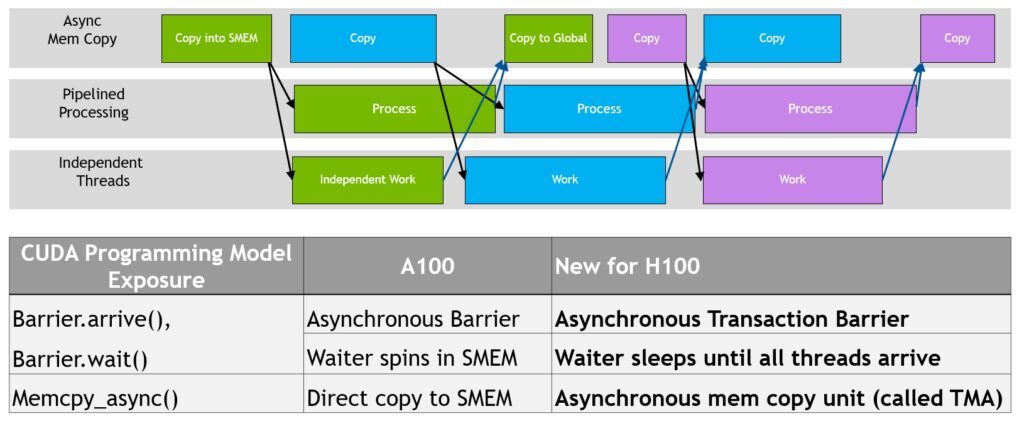

We discussed this briefly in my previous post, but we are approaching more and more towards async producer-consumer paradigms when it comes to GEMM kernels. TMA operations are also asynchronous and use shared-memory–based barriers, where only one thread in a warp issues the cuda::memcpy_async, while others simply wait on the barrier. It frees up threads to perform useful work while data transfers proceed in parallel.

Comparison to A100 and older generation of GPUs

Source: NVIDIA Hopper Architecture in Depth

New way to move data

Source: Developing Optimal CUDA Kernels on Hopper Tensor Cores

Asynchronous Transaction Barriers

Asynchronous barriers were introduced in Ampere and split synchronization into two non-blocking steps: Arrive, where threads signal they’ve finished producing data and can continue doing other work, and Wait, where threads block only when they actually need the results. This overlap boosts performance and we already used this in our previous kernels in pipelined versions in the previous post. In Hopper, waiting threads can now sleep instead of spinning, reducing wasted cycles.

Hopper also has a more advanced primitive called the asynchronous transaction barrier. In addition to Arrive and Wait, it also tracks the amount of data produced. Threads perform Arrive operations that include a transaction (byte) count, and the Wait step blocks until both conditions are met: all threads arrived and the total data produced reaches a specified threshold. These transaction barriers are useful for asynchronous memory operations and efficient data exchange.

Source: Developing Optimal CUDA Kernels on Hopper Tensor Cores

Warp Group Instructions

Hopper also introduced the asynchronous warpgroup-level matrix multiply and accumulate operation (WGMMA). A warpgroup consists of four contiguous warps, i.e., 128 contiguous threads, where the warp-rank of the first warp is a multiple of four. The wgmma.mma_async instruction is executed collectively by all 128 threads in a warpgroup.

The following matrix shapes are supported for bf16 dense computations for the wgmma.mma_async operation:

m64n8k16, m64n16k16, m64n24k16, m64n32k16, m64n40k16, m64n48k16, m64n56k16, m64n64k16, m64n72k16, m64n80k16, m64n88k16, m64n96k16, m64n104k16, m64n112k16, m64n120k16, m64n128k16, m64n136k16, m64n144k16, m64n152k16, m64n160k16, m64n168k16, m64n176k16, m64n184k16, m64n192k16, m64n200k16, m64n208k16, m64n216k16, m64n224k16, m64n232k16, m64n240k16, m64n248k16, m64n256k16

Source: PTX Handbook

Other Features

- Native FP8 Support: H100 also introduced native FP8 (8-bit floating-point) with two formats (E4M3 and E5M2)

- Larger L2 Cache: L2 Cache increase to 50 MB compared to 40 MB

We will ignore the nvlink, nvswitch features since we will just work on a single GPU.

CUTLASS 3.x and Support for Hopper

Before we dive into implementing a Hopper-optimized kernel, let’s quickly look at changes NVIDIA made in CUTLASS 3.x+ to introduce a a new five-layer hierarchy for GEMM Kernels for Hopper+ architectures.

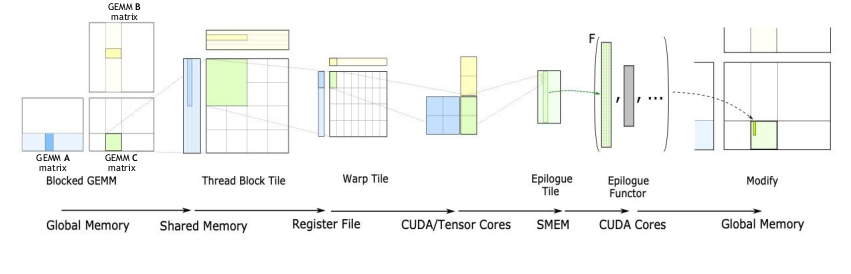

We have previously looked at the GEMM hierarchy as shown below:

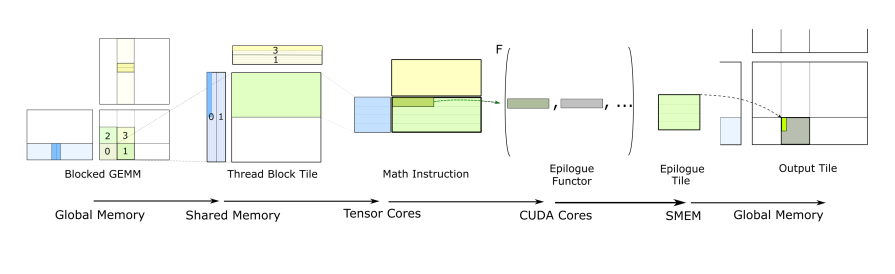

For Hopper and beyond, the API was changed to be centered around conceptual GEMM hierarchy instead of Hardware Hierarchy:

The Collective layer is particularly important for Hopper+ kernels. It’s where temporal micro-kernels orchestrate the producer-consumer pattern we discussed earlier, where producer warps issue TMA loads and consumer warps execute WGMMA operations, all coordinated through asynchronous transaction barriers.

The way this translates into GEMM API is visualized below. For more detailed intro on GEMM API, CUTLASS documentation on CUTLASS 3.x GEMM is pretty useful, though I wished the documentation was a bit better.

Example kernels are useful though. Most useful example in the CUTLASS repo I found was Hopper GEMM with Collective Builder example.

Warp Specialization

Warp specialization (also called spatial partitioning) is a technique where different warps within a thread block are assigned distinct roles rather than executing identical work. Instead of all warps performing the same operations on different data, specialized warps focus on specific tasks i.e. some handle data movement while others perform computation. As GEMMs move to async producer/consumer paradigms, this becomes essential so that a single warp is not holding all the required registers and shared memory resources. It also allows for handling unpredictable cycle counts for memory loads / TMA more efficiently. We will see more paradigms in this later but overall it reduces “empty bubbles” such that some warps can continue executing while others wait on blocking operations.

Simple Warp Specialized Producer-Consumer Pattern

The visualization below shows a simple warp-specialized kernel with one producer and one consumer such that:

- Producer warps initiate asynchronous data transfers (e.g., using

cuda::memcpy_asyncor TMA operations) - Consumer warps perform computations on previously loaded data

- Both groups coordinate using asynchronous barriers

In this arrangement, we overlap memory operations with computation to reduce idle time and improving throughput. Actual timelines can look different depending on memory/compute boundness but this just aims to demostrate the general idea.

TMA Warp Specialized Kernel

Basic/Naive

Let’s start with baseline TMA Warp Specialized version of the Kernel. We will skip basic kernels such as TMA without Warp Specialization since we already know those would end up being slower and is already discussed in some of the other posts linked. Instead, we can start with Hopper specific kernels that provide some reasonable baseline performance.

Let’s look at the most important pieces of the kernel. For the whole kernel, see Full Hopper CUTLASS kernel.

First, we define the Element types and Layouts. We pass RowMajor tensors as is to the kernel.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

using ElementA = cutlass::bfloat16_t;

using ElementB = ElementType;

using ElementC = float;

using ElementD = float;

using ElementAccumulator = float;

// Layouts

using LayoutA = cutlass::layout::RowMajor;

using LayoutB = cutlass::layout::RowMajor;

using LayoutC = cutlass::layout::RowMajor;

using LayoutD = cutlass::layout::RowMajor;

// Alignment (16-byte for TMA)

static constexpr int AlignmentA = 128 / cutlass::sizeof_bits<ElementA>::value;

static constexpr int AlignmentB = 128 / cutlass::sizeof_bits<ElementB>::value;

static constexpr int AlignmentC = 128 / cutlass::sizeof_bits<ElementC>::value;

static constexpr int AlignmentD = 128 / cutlass::sizeof_bits<ElementD>::value;

Next, we define the TileShape and Thread Block Cluster shapes. We use Shape<_1, _1, _1> meaning not using TBC.

1

2

3

// Tile and cluster configuration for H100

using TileShape = Shape<_128, _128, _64>; // CTA tile (M, N, K)

using ClusterShape = Shape<_1, _1, _1>; // Not using Thread block cluster

Next, we define the GEMM Op, which is mostly boilerplate. You can see that we use the KernelSchedule and EpilogueSchedule for TMA warp specialized kernel. For software pipelinining, we start with a 2 Stage Kernel.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

// Warp specialization schedules

using KernelSchedule = cutlass::gemm::KernelTmaWarpSpecialized;

using EpilogueSchedule = cutlass::epilogue::TmaWarpSpecialized;

// Build mainloop collective with automatic stage count calculation

using CollectiveMainloop = typename cutlass::gemm::collective::CollectiveBuilder<

cutlass::arch::Sm90,

cutlass::arch::OpClassTensorOp,

ElementA, LayoutA, AlignmentA,

ElementB, LayoutB, AlignmentB,

ElementAccumulator,

TileShape,

ClusterShape,

cutlass::gemm::collective::StageCount<2>, // 2 stages hard coded

KernelSchedule>::CollectiveOp;

// Build epilogue collective

using CollectiveEpilogue = typename cutlass::epilogue::collective::CollectiveBuilder<

cutlass::arch::Sm90,

cutlass::arch::OpClassTensorOp,

TileShape,

ClusterShape,

cutlass::epilogue::collective::EpilogueTileAuto,

ElementAccumulator,

ElementAccumulator,

ElementC, LayoutC, AlignmentC,

ElementD, LayoutD, AlignmentD,

EpilogueSchedule>::CollectiveOp;

// Assemble the kernel (using non-batched shape)

using GemmKernel = cutlass::gemm::kernel::GemmUniversal<

Shape<int, int, int>,

CollectiveMainloop,

CollectiveEpilogue>;

using Gemm = cutlass::gemm::device::GemmUniversalAdapter<GemmKernel>;

To define the strides, we use the cute utililities provided by cutlass to set the corresponding shapes. Note that {M, K, 1} essentially means M x K matrix since we use number of batches as 1.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

// Problem size (non-batched GEMM)

auto problem_shape = make_shape(M, N, K);

// Stride types for row-major layouts

using StrideA = typename Config::GemmKernel::StrideA;

using StrideB = typename Config::GemmKernel::StrideB;

using StrideC = typename Config::GemmKernel::StrideC;

using StrideD = typename Config::GemmKernel::StrideD;

auto stride_A = cutlass::make_cute_packed_stride(StrideA{}, {M, K, 1});

auto stride_B = cutlass::make_cute_packed_stride(StrideB{}, {N, K, 1});

auto stride_C = cutlass::make_cute_packed_stride(StrideC{}, {M, N, 1});

auto stride_D = cutlass::make_cute_packed_stride(StrideD{}, {M, N, 1});

Let’s see the performance results compared to PyTorch.

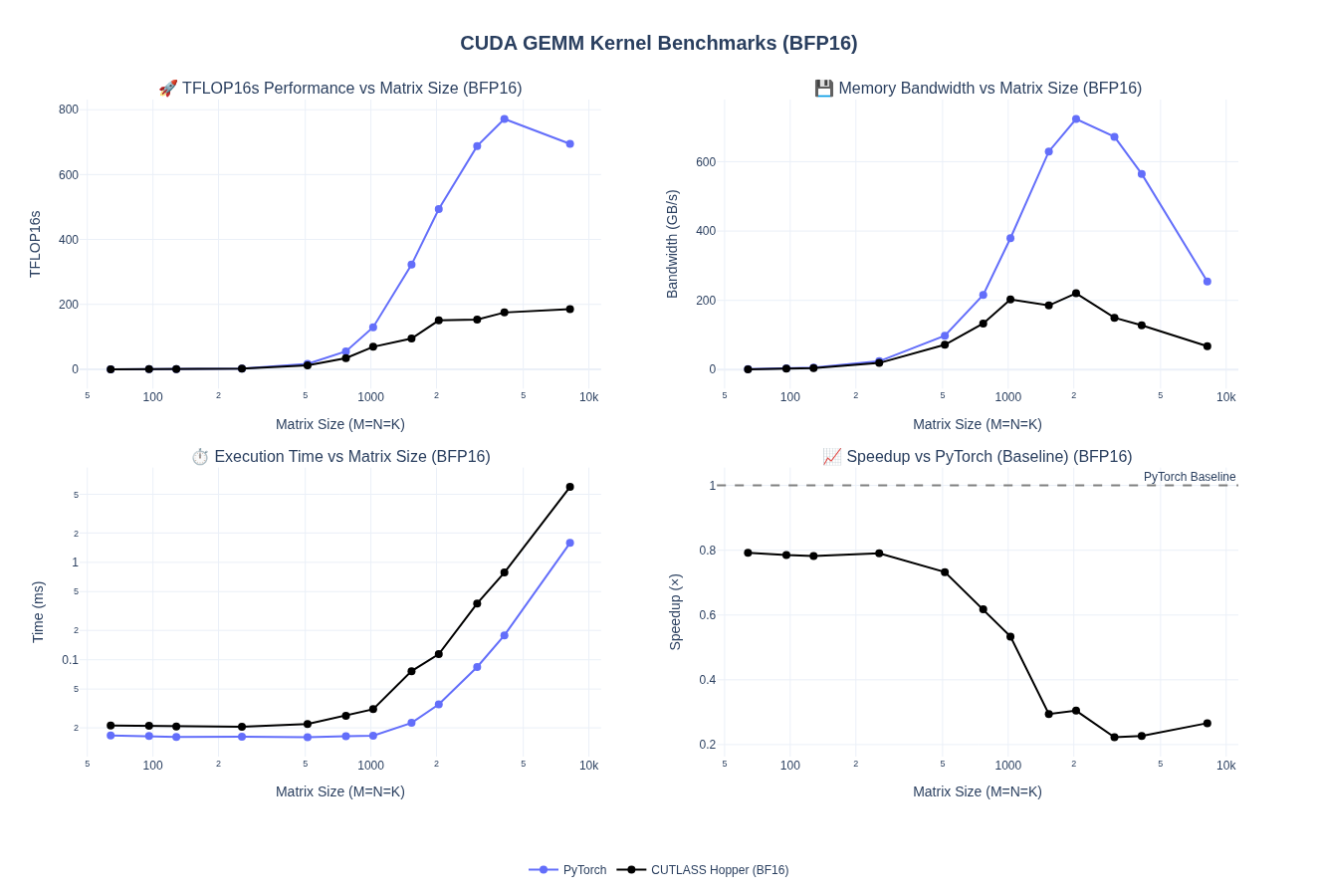

Overall, the performance for large matrices is only about 20-25% - which is actually worse than what we saw with the original CUTLASS 2.x based baseline we tested.

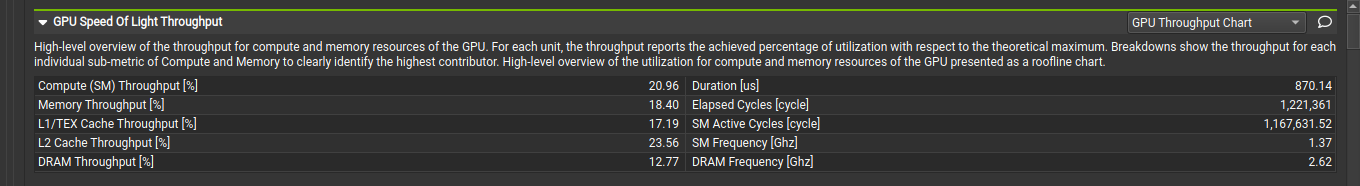

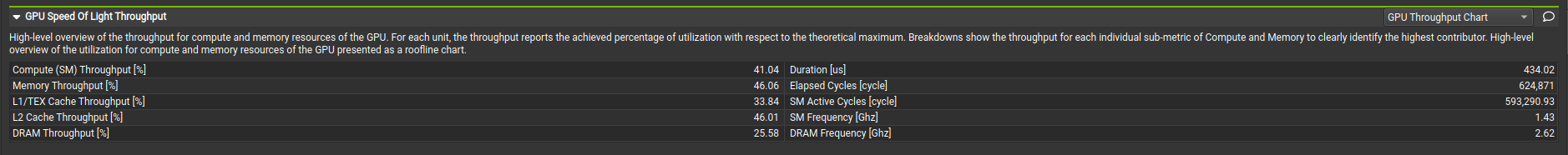

We can see from the Speed of Light analysis in NCU that SM and Memory throughput is pretty bad, as expected.

Increasing/Auto Stage Count

We haven’t tuned anything here, so let’s start with just updating the number of stages from hard-coded value of 2 to Auto. Only thing we need to change is stage argument:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

// Warp specialization schedules

using KernelSchedule = cutlass::gemm::KernelTmaWarpSpecialized;

@@ -57,6 +58,7 @@ struct CutlassHopperGemmConfig

ElementAccumulator,

TileShape,

ClusterShape,

- cutlass::gemm::collective::StageCount<2>, // 2 stages hard coded

+ cutlass::gemm::collective::StageCountAuto,

KernelSchedule>::CollectiveOp;

We pretty much doubled our performance for medium to larger matrices and saw marginal improvements in smaller matrices.

Looking at the NCU Speed of Light profile for size 4096, we can see that increase in TFLOPS is directly proporsional to the SM and Memory throughput.

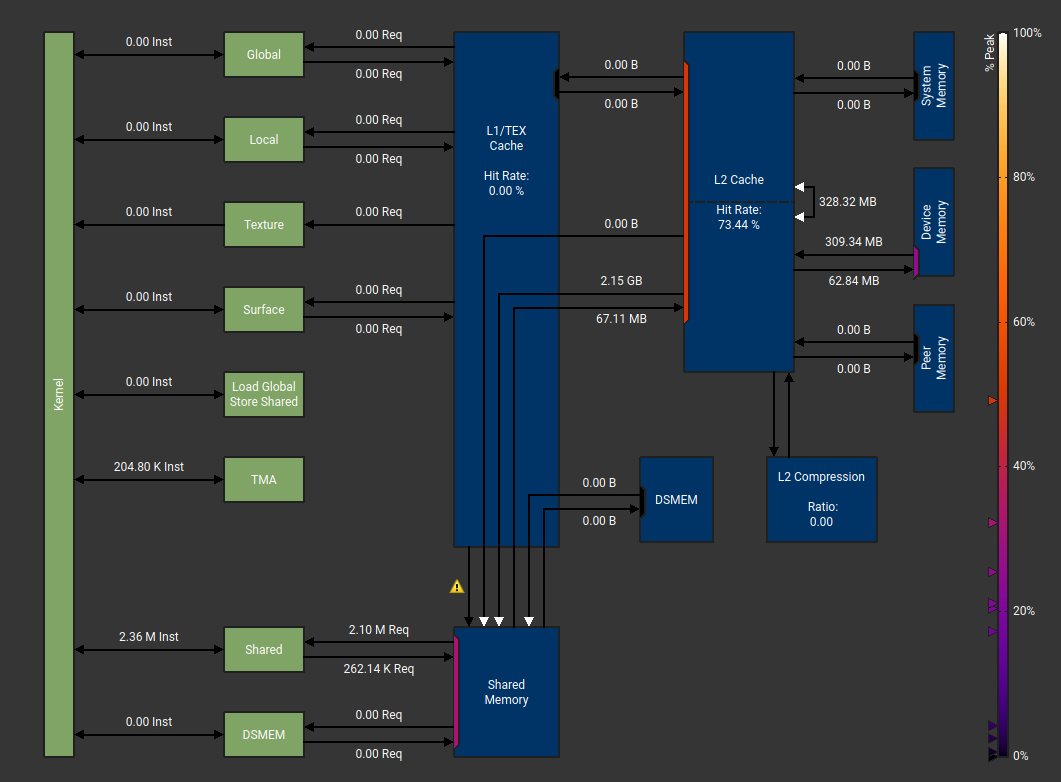

Now, looking at the Memory Chart, I saw the L2 cache hit rate improve to 73% from 63% but nothing much changed. If you noticed previosly, we set the cluster shape to Shape<_1, _1, _1> i.e. we do not share any date across the thread block cluster. This is validated by the 0 input/output from DSMEM.

Hence, a natural place to tune next is use Thread Block Clusters.

Thread Block Cluster

Next, we will test a 1 x 2 x 1 Thread Block Cluster Tile to cooperate across 2 SMs along the reduction dimension. This should allows threads from 2 SMs at a time to be able to share memory across 2 thread blocks.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

--- a/cuda/15_kernel_cutlass_hopper.cu

+++ b/cuda/15_kernel_cutlass_hopper.cu

@@ -42,8 +42,7 @@ struct CutlassHopperGemmConfig

// Tile and cluster configuration for H100

using TileShape = Shape<_128, _128, _64>; // CTA tile (M, N, K)

- using ClusterShape = Shape<_1, _1, _1>; // Not TBC

+ using ClusterShape = Shape<_1, _2, _1>; // Thread block cluster

We see a modest 5% improvement in performance by enabling Thread Block Clusters, which is decent but not much. We are still hovering around 45-55% of Pytorch performance for any batch size > 1024.

A typical warp specialized pipeline might look something like below - here we have 2 producer warps and 2 consumer warps.

Warp-specialized Persistent Cooperative Kernel

The Persistent Cooperative kernel extends basic warp specialization with the following:

Persistent Thread Blocks, launching one thread block per output tile and occupy a fixed number of thread blocks specified in

KernelHardwareInfo. For example, 132 for H100 and each processing multiple tiles. This amortizes kernel launch overhead and improves SM utilization.Two consumer warp groups acting as Cooperative Consumers, which split each output tile in half across the M dimension. This reduces register pressure per consumer, enabling larger tiles that improve arithmetic intensity and cache reuse.

TileSchedulerwill dynamically assigns tiles to persistent thread blocks, considering cluster geometry and SM availability. Thread blocks atomically grab next tiles until the work queue empties.

I initially tried to keep the number of stages as Auto but that led to a runtime error that had no useful. After debugging for a bit, I landed on constant stages = 5

Key changes in the code will look like:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

diff --git a/cuda/15_kernel_cutlass_hopper.cu b/cuda/15_kernel_cutlass_hopper.cu

index f02922c..07b1997 100644

--- a/cuda/15_kernel_cutlass_hopper.cu

+++ b/cuda/15_kernel_cutlass_hopper.cu

@@ -45,8 +45,12 @@ struct CutlassHopperGemmConfig

using ClusterShape = Shape<_1, _2, _1>; // Thread block cluster

// Warp specialization schedules

- using KernelSchedule = cutlass::gemm::KernelTmaWarpSpecialized;

- using EpilogueSchedule = cutlass::epilogue::TmaWarpSpecialized;

+ using KernelSchedule = cutlass::gemm::KernelTmaWarpSpecializedCooperative;

+ using EpilogueSchedule = cutlass::epilogue::TmaWarpSpecializedCooperative;

+ using TileSchedulerType = cutlass::gemm::PersistentScheduler;

// Build mainloop collective with automatic stage count calculation

using CollectiveMainloop = typename cutlass::gemm::collective::CollectiveBuilder<

@@ -57,7 +61,6 @@ struct CutlassHopperGemmConfig

ElementAccumulator,

TileShape,

ClusterShape,

- cutlass::gemm::collective::StageCountAuto,

+ // cutlass::gemm::collective::StageCount<5>,

KernelSchedule>::CollectiveOp;

@@ -78,7 +81,8 @@ struct CutlassHopperGemmConfig

using GemmKernel = cutlass::gemm::kernel::GemmUniversal<

Shape<int, int, int>,

CollectiveMainloop,

- CollectiveEpilogue>;

+ CollectiveEpilogue,

+ TileSchedulerType>;

using Gemm = cutlass::gemm::device::GemmUniversalAdapter<GemmKernel>;

};

Note that we already previously had cutlass::KernelHardwareInfo hw_info, which be useful now.

1

2

3

cutlass::KernelHardwareInfo hw_info;

hw_info.device_id = 0;

hw_info.sm_count = cutlass::KernelHardwareInfo::query_device_multiprocessor_count(hw_info.device_id);

Let’s look at the performance:

We got a nice boost in performance for larger matrices and now our kernel is ranging from 60-70% of PyTorch performance. We are able to achieve upto 480-490 TFLOPS for 4096-8192 batch sizes compared to Pytorch which is in the range of 700-750 TFLOPS.

We observe a regression for smaller matrices that we’ll address later during autotuning when we explore different tile sizes and stage counts optimized for memory-bound workloads.

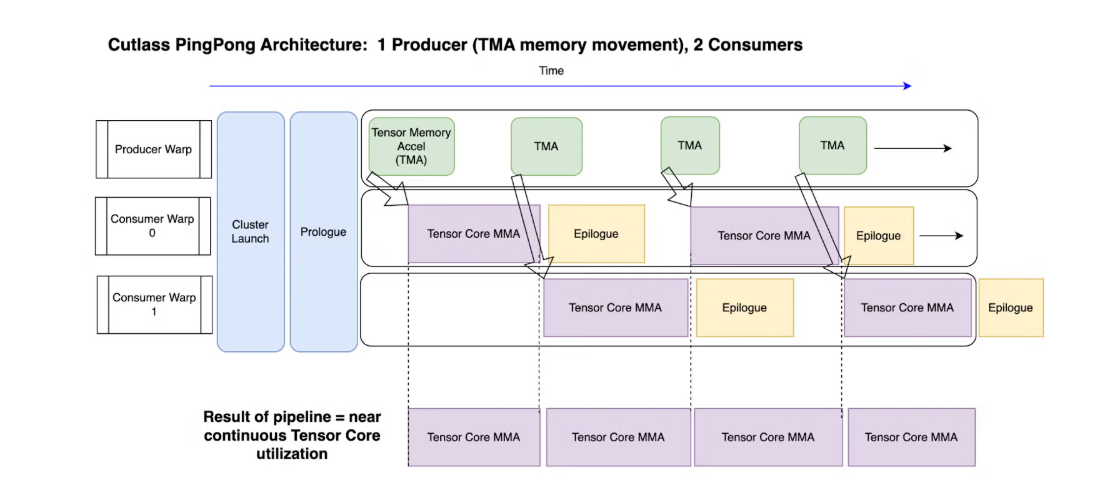

Ping Pong Schedule

The Ping-Pong schedule extends the Cooperative pattern to overlap epilogue with mainloop computation. In Cooperative Schedule, both consumer groups work on the same output tile, sharing A/B buffers. When both finish their MMA operations, tensor cores sit idle during the epilogue (storing results to global memory). This sequential execution leaves performance on the table.

In vanilla persistent cooperative scheduling both consumer Warp Groups have the dependency to the same resources i.e. the smem tile for matrix A/B/C/D since they deal with the same tiles

In Ping-Pong Schedule, the tile scheduler assigns each consumer a different output tile. The producer uses ordered sequence barriers to fill buffers alternately. While consumer 1 executes MMA operations, consumer 2 performs its epilogue. They then swap roles—maximizing tensor core utilization by overlapping computation with memory writes.

We can see that we are able to overlap WGMMA and Epilogue operations across the 2 consumer warps.

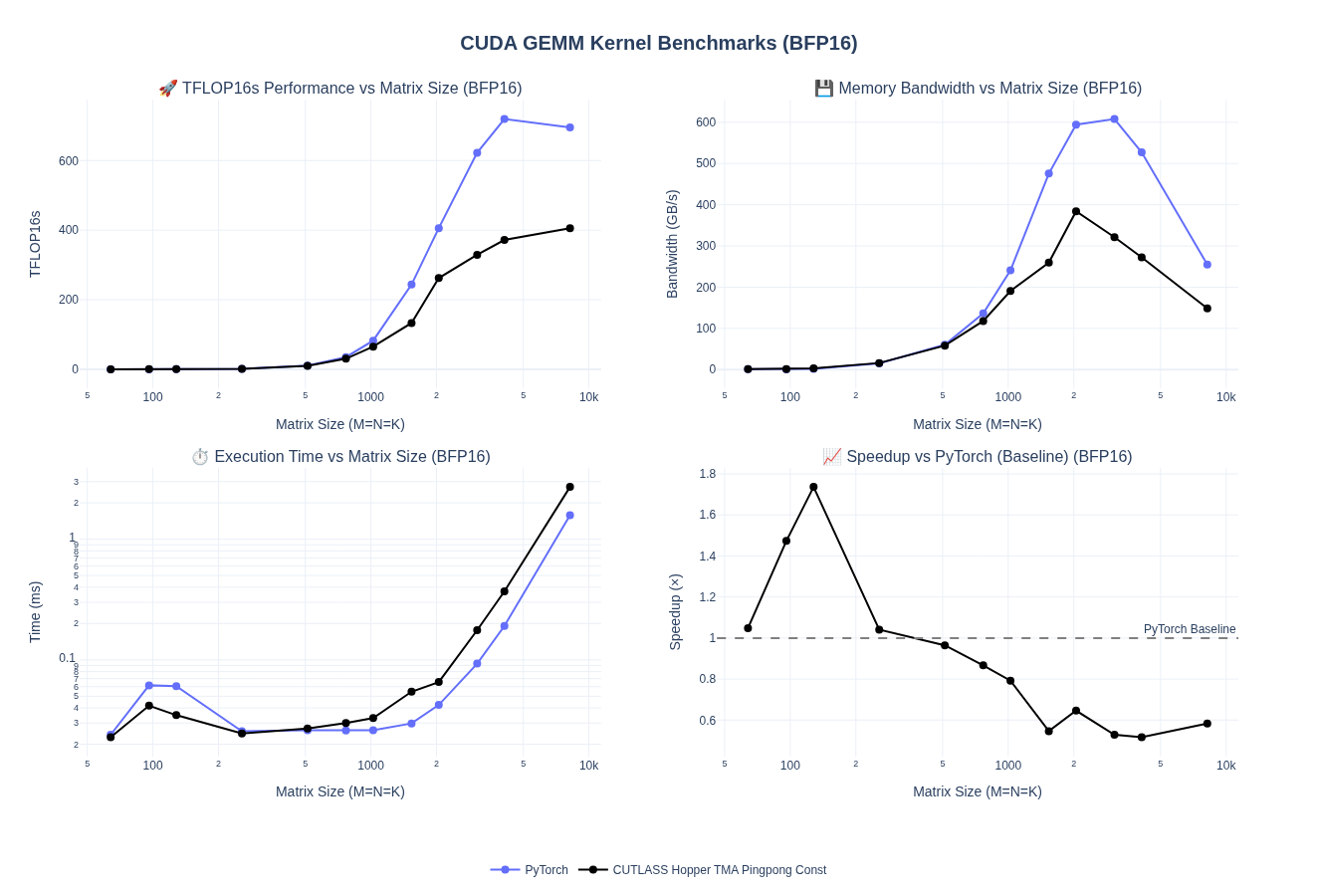

At this point, I expanded the kernel to support multiple kernel configuration and exposed all different kernels to python. Finally, after experimenting a bit, I landed on a ping-pong kernel with stage_count = 5 as being the most performant.

Updated code looks like below - to support multiple combination of configs, I exposed templates for different options

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

306

307

308

309

310

311

312

313

314

315

316

317

318

319

320

321

322

323

324

325

326

327

328

329

330

331

332

333

334

335

336

337

338

339

340

341

342

343

344

345

346

347

348

349

350

351

352

353

354

355

356

357

358

359

360

361

362

363

364

365

366

367

368

369

370

371

372

373

374

375

376

377

378

379

380

381

382

383

384

385

386

387

388

389

390

391

392

393

394

395

396

397

398

399

400

401

402

403

404

405

406

407

408

409

410

411

412

413

414

415

416

417

418

419

420

421

422

423

424

425

426

427

428

429

430

431

432

433

434

435

436

437

438

439

440

441

442

443

444

445

446

447

448

449

450

#include <torch/torch.h>

#include <cuda_runtime.h>

#include "gemm_kernels.cuh"

// CUTLASS 3.x includes for Hopper Collective Builder

#include "cutlass/cutlass.h"

#include "cutlass/numeric_types.h"

#include "cutlass/gemm/device/gemm_universal_adapter.h"

#include "cutlass/gemm/collective/collective_builder.hpp"

#include "cutlass/epilogue/collective/collective_builder.hpp"

#include "cutlass/gemm/kernel/gemm_universal.hpp"

#include "cutlass/util/packed_stride.hpp"

#include "cute/tensor.hpp"

using namespace cute;

// Hopper (SM90) Warp-Specialized GEMM using CUTLASS 3.x Collective Builder API

// Demonstrates TMA (Tensor Memory Accelerator) with warp specialization

// Enum to select different Hopper kernel schedules

enum class HopperKernelType

{

TmaWarpSpecialized, // Basic TMA with warp specialization

TmaWarpSpecializedPersistent, // TMA with persistent scheduling

TmaWarpSpecializedPingpong, // TMA with ping-pong cooperative scheduling

TmaWarpSpecializedStreamK // TMA with Stream K scheduling

};

// Enum to select stage count strategy

enum class StageCountType

{

Auto, // Automatic stage count calculation

Constant // Fixed stage count (5)

};

// Helper function to get kernel schedule type

template <HopperKernelType KernelType, int TileM>

constexpr auto get_kernel_schedule()

{

// For small tiles (TileM < 128), always use basic TmaWarpSpecialized

if constexpr (TileM < 128)

{

return cutlass::gemm::KernelTmaWarpSpecialized{};

}

else if constexpr (KernelType == HopperKernelType::TmaWarpSpecialized)

{

return cutlass::gemm::KernelTmaWarpSpecialized{};

}

else if constexpr (KernelType == HopperKernelType::TmaWarpSpecializedPingpong)

{

return cutlass::gemm::KernelTmaWarpSpecializedPingpong{};

}

else // TmaWarpSpecializedPersistent or TmaWarpSpecializedStreamK

{

return cutlass::gemm::KernelTmaWarpSpecializedCooperative{};

}

}

// Helper function to get epilogue schedule type

template <HopperKernelType KernelType>

constexpr auto get_epilogue_schedule()

{

// Persistent and StreamK variants use cooperative epilogue

if constexpr (KernelType == HopperKernelType::TmaWarpSpecializedPersistent ||

KernelType == HopperKernelType::TmaWarpSpecializedStreamK)

{

return cutlass::epilogue::TmaWarpSpecializedCooperative{};

}

else

{

return cutlass::epilogue::TmaWarpSpecialized{};

}

}

// Helper function to get tile scheduler type

template <HopperKernelType KernelType>

constexpr auto get_tile_scheduler()

{

if constexpr (KernelType == HopperKernelType::TmaWarpSpecialized)

{

return; // void - no tile scheduler

}

else if constexpr (KernelType == HopperKernelType::TmaWarpSpecializedStreamK)

{

return cutlass::gemm::StreamKScheduler{};

}

else

{

return cutlass::gemm::PersistentScheduler{};

}

}

// Helper function to get stage count type

template <StageCountType StageType, typename ElementA, int Stages = 5>

constexpr auto get_stage_count()

{

// Validate: Auto requires Stages == -1, Constant requires Stages > 0

static_assert((StageType == StageCountType::Auto && Stages == -1) ||

(StageType == StageCountType::Constant && Stages > 0),

"When StageType is Auto, Stages must be -1; when Constant, Stages must be > 0");

if constexpr (StageType == StageCountType::Auto)

{

return cutlass::gemm::collective::StageCountAutoCarveout<sizeof(ElementA)>{};

}

else

{

return cutlass::gemm::collective::StageCount<Stages>{};

}

}

template <typename ElementType, HopperKernelType KernelType, StageCountType StageType, int NumStages = -1>

struct CutlassHopperGemmConfig

{

// Validate stage count configuration: Auto requires NumStages == -1, Constant requires NumStages > 0

static_assert((StageType == StageCountType::Auto && NumStages == -1) ||

(StageType == StageCountType::Constant && NumStages > 0),

"When StageType is Auto, NumStages must be -1; when Constant, NumStages must be > 0");

// Element types

using ElementA = ElementType;

using ElementB = ElementType;

using ElementC = ElementType;

using ElementD = ElementType;

using ElementAccumulator = float;

// Layouts

using LayoutA = cutlass::layout::RowMajor;

using LayoutB = cutlass::layout::RowMajor;

using LayoutC = cutlass::layout::RowMajor;

using LayoutD = cutlass::layout::RowMajor;

// Alignment (16-byte for TMA)

static constexpr int AlignmentA = 128 / cutlass::sizeof_bits<ElementA>::value;

static constexpr int AlignmentB = 128 / cutlass::sizeof_bits<ElementB>::value;

static constexpr int AlignmentC = 128 / cutlass::sizeof_bits<ElementC>::value;

static constexpr int AlignmentD = 128 / cutlass::sizeof_bits<ElementD>::value;

// Tile and cluster configuration for H100

static constexpr int TileM = 128;

// TileN depends on NumStages: use 256 if stages 1-3, otherwise 128

static constexpr int TileN = (StageType == StageCountType::Constant && NumStages >= 1 && NumStages <= 3) ? 256 : 128;

static constexpr int TileK = 64;

using TileShape = Shape<cute::Int<TileM>, cute::Int<TileN>, cute::Int<TileK>>; // CTA tile (M, N, K)

using ClusterShape = Shape<_2, _1, _1>;

// Select kernel schedule, epilogue schedule, tile scheduler, and stage count using constexpr if

using KernelSchedule = decltype(get_kernel_schedule<KernelType, TileM>());

using EpilogueSchedule = decltype(get_epilogue_schedule<KernelType>());

using TileSchedulerType = decltype(get_tile_scheduler<KernelType>());

using StageCount = decltype(get_stage_count<StageType, ElementA, NumStages>());

// Build mainloop collective

using CollectiveMainloop = typename cutlass::gemm::collective::CollectiveBuilder<

cutlass::arch::Sm90,

cutlass::arch::OpClassTensorOp,

ElementA, LayoutA, AlignmentA,

ElementB, LayoutB, AlignmentB,

ElementAccumulator,

TileShape,

ClusterShape,

StageCount,

KernelSchedule>::CollectiveOp;

// Build epilogue collective

using CollectiveEpilogue = typename cutlass::epilogue::collective::CollectiveBuilder<

cutlass::arch::Sm90,

cutlass::arch::OpClassTensorOp,

TileShape,

ClusterShape,

cutlass::epilogue::collective::EpilogueTileAuto,

ElementAccumulator,

ElementAccumulator,

ElementC, LayoutC, AlignmentC,

ElementD, LayoutD, AlignmentD,

EpilogueSchedule>::CollectiveOp;

// Helper to create the appropriate GemmKernel type

template <typename Scheduler>

static auto make_gemm_kernel_type()

{

if constexpr (std::is_void_v<Scheduler>)

{

return cutlass::gemm::kernel::GemmUniversal<

Shape<int, int, int>,

CollectiveMainloop,

CollectiveEpilogue>{};

}

else

{

return cutlass::gemm::kernel::GemmUniversal<

Shape<int, int, int>,

CollectiveMainloop,

CollectiveEpilogue,

Scheduler>{};

}

}

// Assemble the kernel - different signature based on whether we have a tile scheduler

using GemmKernel = decltype(make_gemm_kernel_type<TileSchedulerType>());

using Gemm = cutlass::gemm::device::GemmUniversalAdapter<GemmKernel>;

};

// Type aliases for different kernel configurations

// TMA Warp Specialized variants

template <typename ElementType, int NumStages = -1>

using TmaWarpSpecializedAutoConfig = CutlassHopperGemmConfig<ElementType, HopperKernelType::TmaWarpSpecialized, StageCountType::Auto, NumStages>;

template <typename ElementType, int NumStages = 5>

using TmaWarpSpecializedConstantConfig = CutlassHopperGemmConfig<ElementType, HopperKernelType::TmaWarpSpecialized, StageCountType::Constant, NumStages>;

// TMA Warp Specialized Persistent variants

template <typename ElementType, int NumStages = -1>

using TmaWarpSpecializedPersistentAutoConfig = CutlassHopperGemmConfig<ElementType, HopperKernelType::TmaWarpSpecializedPersistent, StageCountType::Auto, NumStages>;

template <typename ElementType, int NumStages = 5>

using TmaWarpSpecializedPersistentConstantConfig = CutlassHopperGemmConfig<ElementType, HopperKernelType::TmaWarpSpecializedPersistent, StageCountType::Constant, NumStages>;

// TMA Warp Specialized Pingpong variants

template <typename ElementType, int NumStages = -1>

using TmaWarpSpecializedPingpongAutoConfig = CutlassHopperGemmConfig<ElementType, HopperKernelType::TmaWarpSpecializedPingpong, StageCountType::Auto, NumStages>;

template <typename ElementType, int NumStages = 5>

using TmaWarpSpecializedPingpongConstantConfig = CutlassHopperGemmConfig<ElementType, HopperKernelType::TmaWarpSpecializedPingpong, StageCountType::Constant, NumStages>;

// TMA Warp Specialized Stream-K variants

template <typename ElementType, int NumStages = -1>

using TmaWarpSpecializedStreamKAutoConfig = CutlassHopperGemmConfig<ElementType, HopperKernelType::TmaWarpSpecializedStreamK, StageCountType::Auto, NumStages>;

template <typename ElementType, int NumStages = 3>

using TmaWarpSpecializedStreamKConstantConfig = CutlassHopperGemmConfig<ElementType, HopperKernelType::TmaWarpSpecializedStreamK, StageCountType::Constant, NumStages>;

// BF16 type aliases for all 8 variants

using BF16HopperTmaWarpSpecializedAuto = TmaWarpSpecializedAutoConfig<bfloat16_t>;

using BF16HopperTmaWarpSpecializedConstant = TmaWarpSpecializedConstantConfig<bfloat16_t>;

using BF16HopperTmaWarpSpecializedPersistentAuto = TmaWarpSpecializedPersistentAutoConfig<bfloat16_t>;

using BF16HopperTmaWarpSpecializedPersistentConstant = TmaWarpSpecializedPersistentConstantConfig<bfloat16_t>;

using BF16HopperTmaWarpSpecializedPingpongAuto = TmaWarpSpecializedPingpongAutoConfig<bfloat16_t>;

using BF16HopperTmaWarpSpecializedPingpongConstant = TmaWarpSpecializedPingpongConstantConfig<bfloat16_t>;

using BF16HopperTmaWarpSpecializedStreamKAuto = TmaWarpSpecializedStreamKAutoConfig<bfloat16_t>;

using BF16HopperTmaWarpSpecializedStreamKConstant = TmaWarpSpecializedStreamKConstantConfig<bfloat16_t>;

// Helper to check if scheduler is Stream-K

template <typename Scheduler>

struct is_streamk_scheduler : std::false_type {};

template <>

struct is_streamk_scheduler<cutlass::gemm::StreamKScheduler> : std::true_type {};

template <typename Config>

cudaError_t cutlass_hopper_gemm_launch(

int M, int N, int K,

const typename Config::ElementA *d_A, int lda,

const typename Config::ElementB *d_B, int ldb,

typename Config::ElementD *d_D, int ldd,

cudaStream_t stream = nullptr)

{

if (M == 0 || N == 0 || K == 0)

return cudaSuccess;

typename Config::Gemm gemm_op;

// Problem size (non-batched GEMM)

auto problem_shape = make_shape(M, N, K);

// Stride types for row-major layouts

using StrideA = typename Config::GemmKernel::StrideA;

using StrideB = typename Config::GemmKernel::StrideB;

using StrideC = typename Config::GemmKernel::StrideC;

using StrideD = typename Config::GemmKernel::StrideD;

auto stride_A = cutlass::make_cute_packed_stride(StrideA{}, {M, K, 1});

auto stride_B = cutlass::make_cute_packed_stride(StrideB{}, {K, N, 1});

auto stride_C = cutlass::make_cute_packed_stride(StrideC{}, {M, N, 1});

auto stride_D = cutlass::make_cute_packed_stride(StrideD{}, {M, N, 1});

// Hardware info

cutlass::KernelHardwareInfo hw_info;

hw_info.device_id = 0;

hw_info.sm_count = cutlass::KernelHardwareInfo::query_device_multiprocessor_count(hw_info.device_id);

// Hard-coded alpha = 1.0, beta = 0.0

float alpha = 1.0f;

float beta = 0.0f;

// Create arguments - different for Stream-K vs other schedulers

typename Config::Gemm::Arguments args = [&]() {

if constexpr (is_streamk_scheduler<typename Config::TileSchedulerType>::value)

{

// Stream-K scheduler requires additional arguments

using DecompositionMode = typename cutlass::gemm::kernel::detail::PersistentTileSchedulerSm90StreamKParams::DecompositionMode;

// Stream-K decomposition mode

DecompositionMode decomp = DecompositionMode::StreamK;

// Number of splits (1 for default Stream-K behavior)

int splits = 1;

// Scheduler arguments: splits, swizzle_mode, raster_order, decomposition_mode

typename Config::GemmKernel::TileScheduler::Arguments scheduler_args{

splits,

static_cast<int>(cutlass::gemm::kernel::detail::PersistentTileSchedulerSm90::RasterOrder::AlongN),

cutlass::gemm::kernel::detail::PersistentTileSchedulerSm90::RasterOrderOptions::Heuristic,

decomp

};

return typename Config::Gemm::Arguments{

cutlass::gemm::GemmUniversalMode::kGemm,

problem_shape,

{d_A, stride_A, d_B, stride_B}, // Mainloop args

{ {alpha, beta}, d_D, stride_C, d_D, stride_D}, // Epilogue args

hw_info,

scheduler_args // Stream-K scheduler args

};

}

else if constexpr (std::is_void_v<typename Config::TileSchedulerType>)

{

// No tile scheduler (basic TMA Warp Specialized)

return typename Config::Gemm::Arguments{

cutlass::gemm::GemmUniversalMode::kGemm,

problem_shape,

{d_A, stride_A, d_B, stride_B}, // Mainloop args

{ {alpha, beta}, d_D, stride_C, d_D, stride_D}, // Epilogue args

hw_info

};

}

else

{

// Persistent scheduler (no additional args needed beyond hw_info)

return typename Config::Gemm::Arguments{

cutlass::gemm::GemmUniversalMode::kGemm,

problem_shape,

{d_A, stride_A, d_B, stride_B}, // Mainloop args

{ {alpha, beta}, d_D, stride_C, d_D, stride_D}, // Epilogue args

hw_info

};

}

}();

// Check if the problem size is supported

cutlass::Status status = gemm_op.can_implement(args);

if (status != cutlass::Status::kSuccess)

{

return cudaErrorNotSupported;

}

// Initialize the kernel

size_t workspace_size = Config::Gemm::get_workspace_size(args);

void *workspace = nullptr;

if (workspace_size > 0)

{

cudaError_t result = cudaMalloc(&workspace, workspace_size);

if (result != cudaSuccess)

return result;

}

status = gemm_op.initialize(args, workspace, stream);

if (status != cutlass::Status::kSuccess)

{

if (workspace)

cudaFree(workspace);

return cudaErrorUnknown;

}

// Run the kernel

status = gemm_op.run(stream);

// Free workspace

if (workspace)

cudaFree(workspace);

if (status != cutlass::Status::kSuccess)

return cudaErrorUnknown;

return cudaSuccess;

}

template <typename Config, typename TorchType>

void cutlass_hopper_gemm_pytorch_wrapper(

const torch::Tensor &matrix_a,

const torch::Tensor &matrix_b,

torch::Tensor &output_matrix,

const char *dtype_name,

const at::ScalarType expected_type)

{

// Validate input tensors

TORCH_CHECK(matrix_a.device().is_cuda(), "Matrix A must be on CUDA device");

TORCH_CHECK(matrix_b.device().is_cuda(), "Matrix B must be on CUDA device");

TORCH_CHECK(output_matrix.device().is_cuda(), "Output matrix must be on CUDA device");

TORCH_CHECK(matrix_a.scalar_type() == expected_type, "Matrix A must be ", dtype_name);

TORCH_CHECK(matrix_b.scalar_type() == expected_type, "Matrix B must be ", dtype_name);

// TORCH_CHECK(output_matrix.scalar_type() == at::kFloat, "Output matrix must be float32");

TORCH_CHECK(matrix_a.dim() == 2 && matrix_b.dim() == 2, "A and B must be 2D tensors");

TORCH_CHECK(matrix_a.is_contiguous() && matrix_b.is_contiguous(),

"Input tensors must be contiguous for alignment requirements");

TORCH_CHECK(output_matrix.is_contiguous(), "Output tensor must be contiguous");

// Extract dimensions

const int M = static_cast<int>(matrix_a.size(0));

const int K = static_cast<int>(matrix_a.size(1));

const int N = static_cast<int>(matrix_b.size(1));

TORCH_CHECK(matrix_b.size(0) == K, "Matrix dimension mismatch");

TORCH_CHECK(output_matrix.size(0) == M && output_matrix.size(1) == N,

"Output matrix has wrong shape");

// Check alignment requirements (16-byte alignment for TMA)

TORCH_CHECK(reinterpret_cast<uintptr_t>(matrix_a.data_ptr()) % 16 == 0,

"Matrix A must be 16-byte aligned for Hopper TMA");

TORCH_CHECK(reinterpret_cast<uintptr_t>(matrix_b.data_ptr()) % 16 == 0,

"Matrix B must be 16-byte aligned for Hopper TMA");

TORCH_CHECK(reinterpret_cast<uintptr_t>(output_matrix.data_ptr()) % 16 == 0,

"Output matrix must be 16-byte aligned for Hopper TMA");

// Get device pointers

const auto *d_A =

reinterpret_cast<const typename Config::ElementA *>(matrix_a.data_ptr<TorchType>());

const auto *d_B =

reinterpret_cast<const typename Config::ElementB *>(matrix_b.data_ptr<TorchType>());

auto *d_D = reinterpret_cast<typename Config::ElementD *>(output_matrix.data_ptr<TorchType>());

int lda = K;

int ldb = N;

int ldd = N;

cudaStream_t stream = nullptr;

// Launch CUTLASS Hopper GEMM (alpha=1.0, beta=0.0 hard-coded)

const cudaError_t err = cutlass_hopper_gemm_launch<Config>(

M, N, K, d_A, lda, d_B, ldb, d_D, ldd, stream);

// Synchronize to catch any kernel launch errors

if (err == cudaSuccess) {

cudaError_t sync_err = cudaDeviceSynchronize();

TORCH_CHECK(sync_err == cudaSuccess,

"CUTLASS Hopper GEMM (", dtype_name, ") kernel execution failed: ",

cudaGetErrorString(sync_err));

}

TORCH_CHECK(err == cudaSuccess,

"CUTLASS Hopper GEMM (", dtype_name, ") launch failed: ", cudaGetErrorString(err));

}

// skipping the individual kernel wrappers since those looks pretty much the same

On benchmarks, I actually saw a degradation in performance when I switched to pingpong scheduler and was not able to match the performance of Bert’s results in simplegemm. But, I hadn’t done any swizzling patterns and more detailed autotuning yet so I figured to push the performance further I needed add those in. But anyhow, here are the results where we can barely hit 400 TFLOPs for 8192 batch sizes.

Stream-K Scheduling

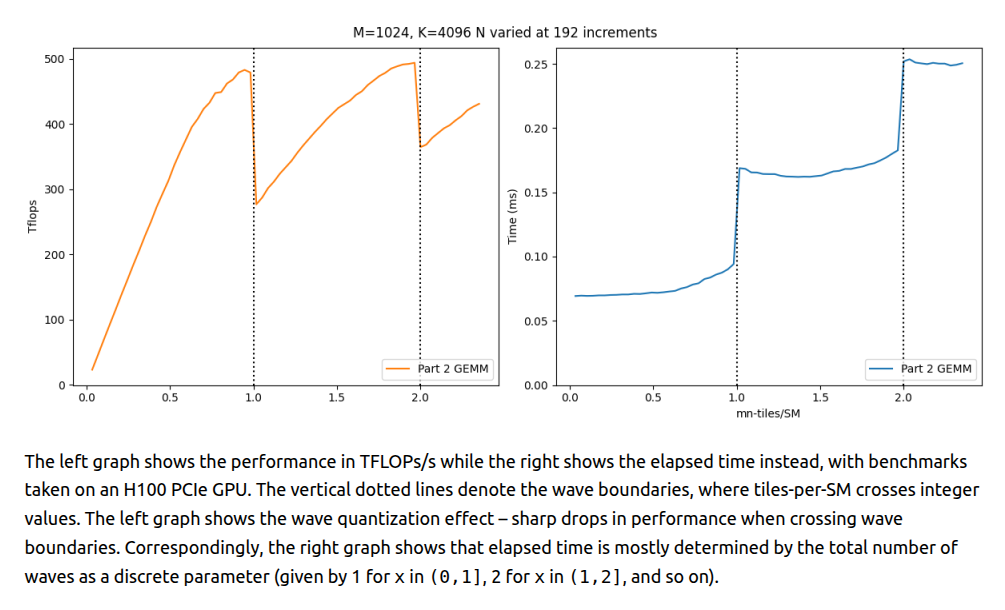

Wave Quantization Problem

Standard GEMM kernels partition output tiles across SMs in discrete waves when the number of work units exceeds number of available SMs. Hence, when work tiles don’t divide evenly by SM count, the final partial wave leaves SMs idle i.e. wave quantization.

For example, on H100 SXM5 with 132 SMs, computing 133 tiles requires 2 full waves i.e. identical cost to computing 264 tiles. The 133rd tile effectively halves device utilization.

For more details, see prior work from Colfax Research on this:

Source: CUTLASS Tutorial: Persistent Kernels and Stream-K

So how do we solve this?

Data-Parallel Approach

The most direct solution is to reduce tile size and creating more work units to fill partial waves. In our 4 SM example above, this would create 18 tiles instead of 9, improving utilization from 75% to 90%. However, smaller tiles degrade efficiency due to loss of arithmetic intensity (refer to tiling sections from prevous post). In essense, this will reduce latency-hiding opportunities for the warp scheduler. Hence, While data-parallel tiling improves wave balance, the per-tile performance loss often negates any gains.

Split-K Partitioning (Along Reduction Dimension)

Next natural extenstion here is Split-K, where we could divide tiles along the K-dimension into a constant number of pieces (e.g., splitting a 128×128×128 tile into two 128×128×64 pieces). Unlike splitting M or N, this increases work units without shrinking output tile dimensions. This can preserve arithmetic intensity better than data-parallel approach. Since each CTA accumulates only partial results for its output tile, CTAs collaborating on the same tile perform turnstile reduction in a global memory workspace such that each waits at a barrier for CTAs processing earlier K-slices, reduces its partial results into the workspace, then signals completion. The final CTA reduces from the workspace to accumulators and executes the epilogue.

More splits improve wave balance but degrade K-tile efficiency (lower arithmetic intensity, fewer latency-hiding opportunities) and increase synchronization overhead (barriers + GMEM traffic). Hence sweet spot depends on problem and hardware specific tuning.

Stream-K: Fractional Tile Assignment

That brings us to Stream-K, which aims to eliminate wave quantization completely by assigning each persistent CTA a fractional number of work tiles. In our 9-tile, 4-SM example, each SM computes exactly 2.25 tiles instead of discrete waves. SM0 processes tiles 0, 1, and ¼ of tile 2; SM1 completes tile 2, processes tile 3, and starts half of tile 4. Split tiles partition along K-dimension using turnstile reduction (like Split-K), but with temporal scheduling—early K-pieces compute well before final pieces, minimizing barrier wait times.

This eliminates quantization entirely. Total time approaches 2.25 work units (vs 3 waves in the naive approach) with only minimal synchronization overhead. Most original 128×128×128 tiles remain intact, maintaining high arithmetic intensity and full WGMMA instruction availability. Temporal scheduling ensures epilogue-computing CTAs rarely wait i.e. earlier collaborators finish K-slices far in advance. The trade-off is additional GMEM workspace for partial tile sharing between CTAs, similar to Split-K but with the better load balancing.

Hybrid Stream-K: Fixing the Cache Problem

While Stream-K eliminates wave quantization, it introduces temporal skew that hurts L2 cache performance. In data-parallel scheduling, CTAs working on adjacent output tiles simultaneously request the same K-blocks of shared operand tiles (e.g., tiles 0, 1, 2 all need B0), creating cache hits. Stream-K’s fractional assignments break this synchronization i.e. CTAs request different K-offsets at different times. Hybrid Stream-K fixes this by partitioning work into two phases. First, the Stream-K phase processes exactly 1 full wave + the partial wave using fractional tiles. Each CTA receives at most 2 partial tiles totaling the same work, ensuring all CTAs finish this phase simultaneously.

Second, the data-parallel phase executes remaining complete tiles (divisible by SM count) with standard scheduling. CTAs now process adjacent output tiles in sync, restoring cache locality for shared A/B tiles. This hybrid approach eliminates quantization via Stream-K phase while maximizing cache hits via data-parallel phase for the bulk of computation.

For more details and in-depth discussion refer to CUTLASS Tutorial: Persistent Kernels and Stream-K.

NOTE: I did not implement the Hybrid Stream-K. Results below are for Stream-K configuration.

Performance Results

We are able to break into the 500+ TFLOPs now. I had to reduce the stage count to 3 to get the best performance for 8192 batch sizes with stream-K enabled. We can see the performance degraded for some smaller batch sizes. In the next few sections, we will do a full autotune to get those sorted out.

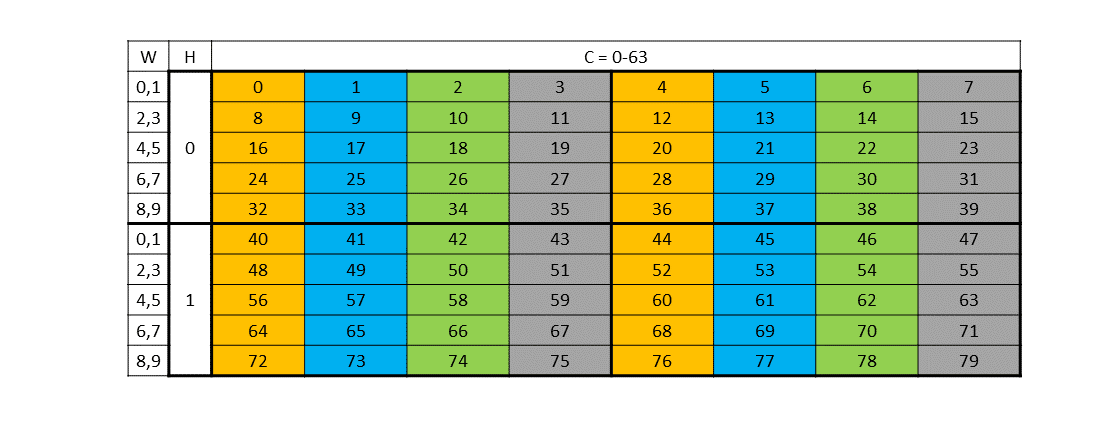

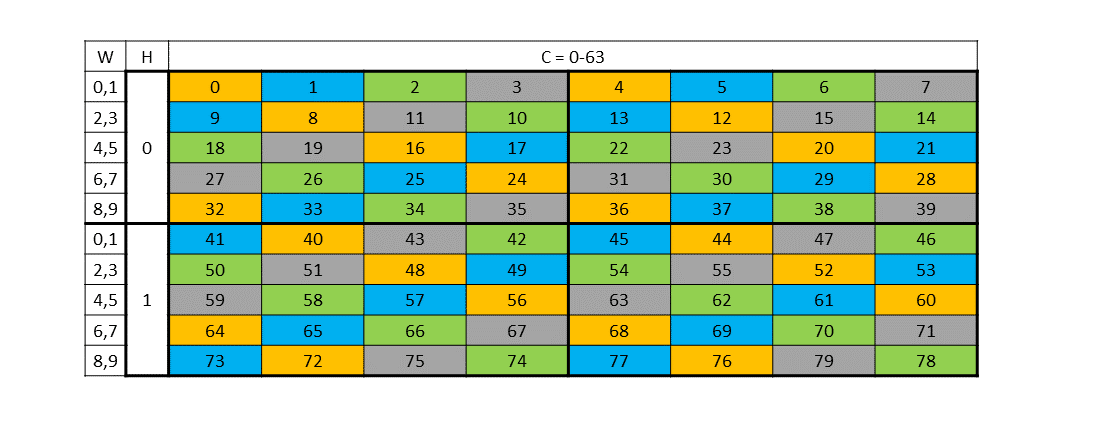

CTA Rasterization and Swizzle

We discussed rasterization and swizzling in the previous blog post but we will cover it a bit more here. CTA rasterization defines the order in which thread blocks map to GEMM tiles and are executed on the GPU. We want logical work tiles to be close to each other on the physical hardware. A naive row-major launch often leads to poor L2 reuse and redundant global loads since you end up needing to reload same data along one dimension over and over into cache.

On top of rasterization, swizzling allows us to further remap the scan order into an intentional remapping of shared memory locations to minimize bank conflict. As we previously covered, CTA swizzling remaps (blockIdx.x, blockIdx.y) to improve spatial and temporal locality across tiles. For more details, read Bank Conflicts and Swizzling section in the previous post.

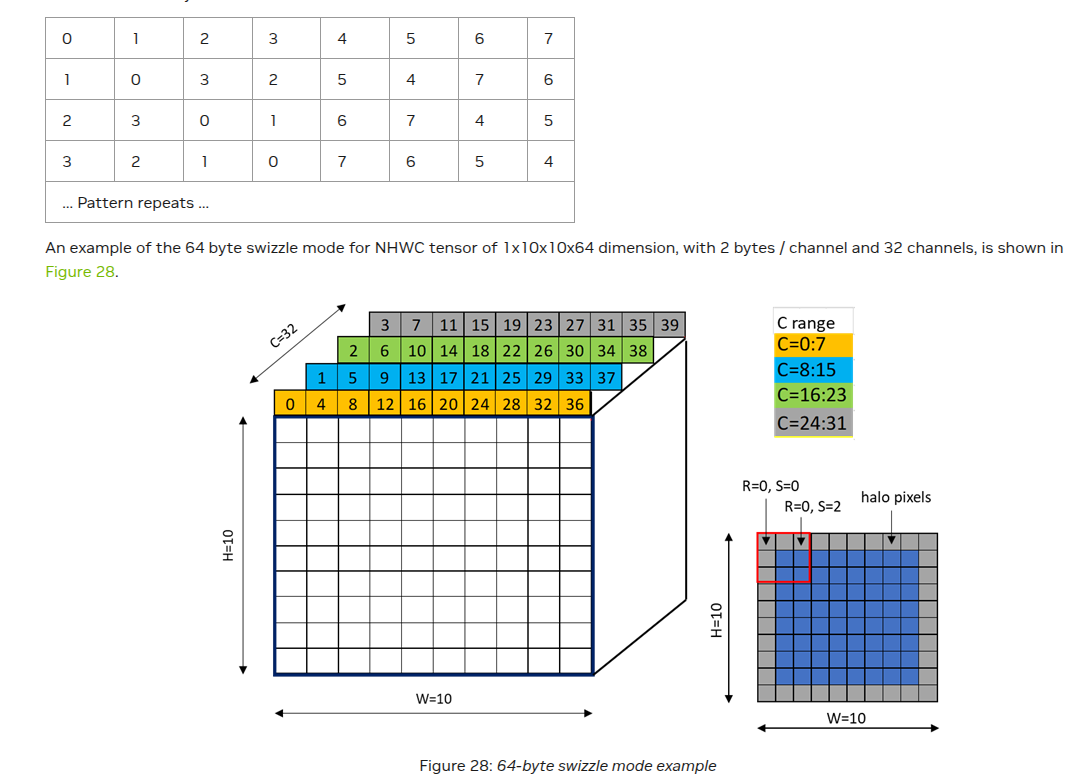

PTX Docs have a really nice visualizations of swizzling patterns

Example: 32-Byte Swizzle

Let’s take example of 32-byte swizzling on an 8x8 grid. Since we have 32 banks and each cell represents 4 bytes, banks will start conflicting after 32 elements. In case we were looking at bf16/fp16 values, the banks will repeat after 64 elements. Just simple math. So, in this case we will have 2-way bank conflict i.e. each column of 8 elements has access to 4 unique banks. To solve, we will remap the memory addresses such that we can shuffle values around to make sure each column has access to 8 unique banks. To get the swizzled address, we will get:

1

2

// XOR the row index with column bits to scramble bank assignment:

swizzled_address = (row * stride) + (col ^ ((row & 7) << 2))

Same column now spreads across different banks → no conflicts!

What really made swizzling tick for me was reading and staring at the swizzled grids in the PTX docs. I will leave a few more examples of swizzling below to showcase how this extends to 64-byte and 128-byte swizzling.

64-byte swizzling

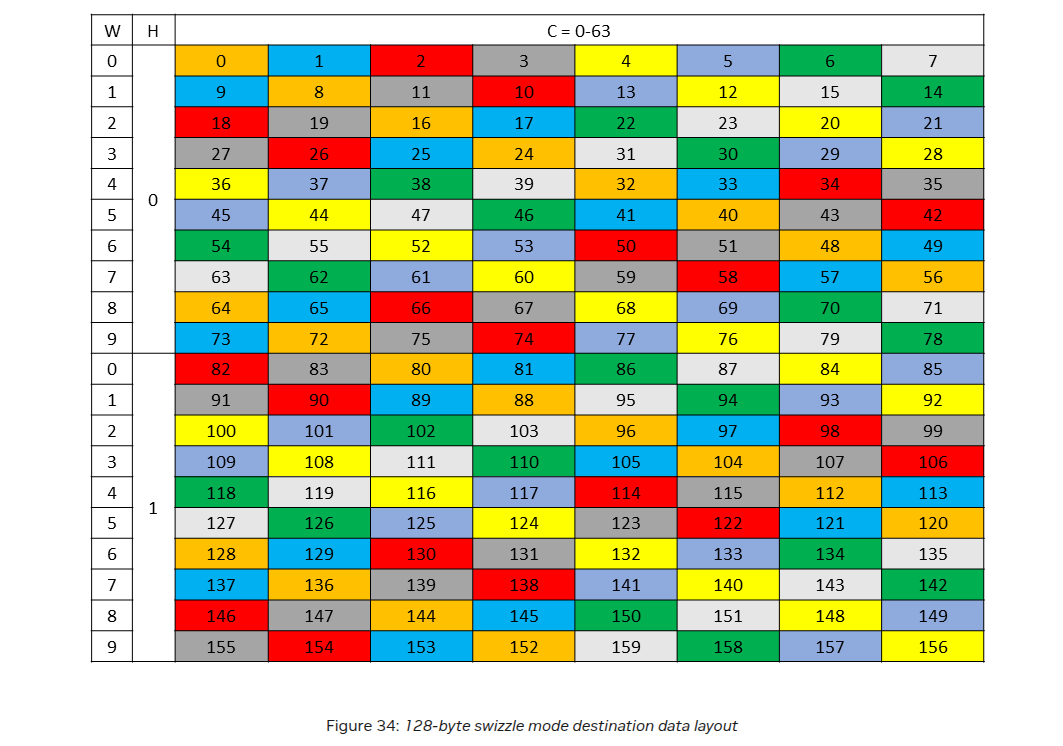

128-byte swizzling

Few more resources on swizzling: Simons Blog, Lei Mao’s blog, bertmaher/simplegemm

Since rasterization and swizzling was the last configuration change I was going to make, I decided to just incorporate everything in an autotune script. I was also able to push the tile sizes to 128x256x64 for the larger shapes to get some speedups as well. Let’s see all the results below!

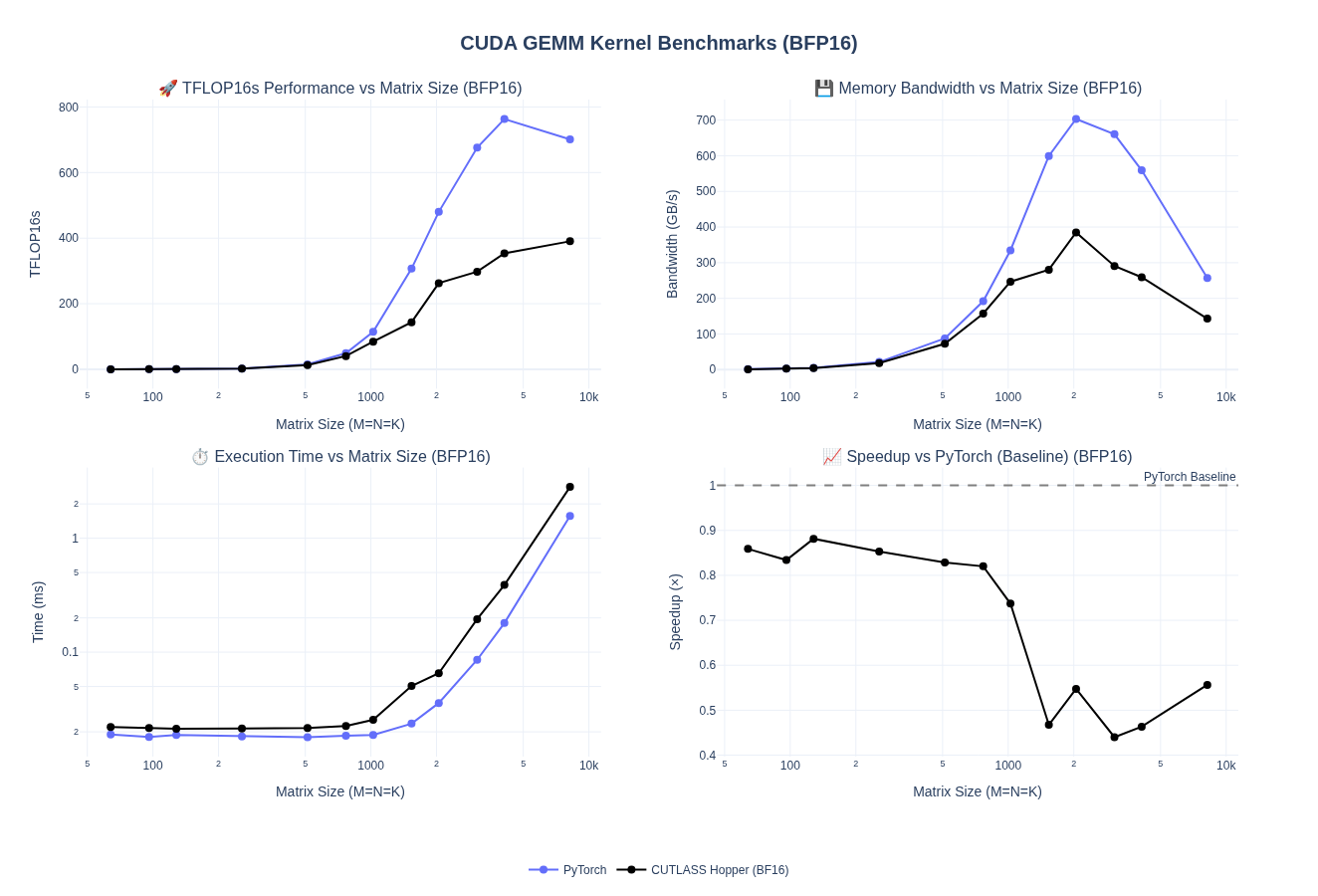

Final YOLO Autotuning Run

After incorporating all the different configuration options, I ran 1300+ different combinations of kernels to get a sense of how the performance is affected by each and combination of them.

Overall we are able to now hit 90% of PyTorch performance for the larger sizes: 4096 to 8192. We can way exceed PyTorch performance for smaller batch sizes where are we are still in memory-bound regimes.

NOTE: In all the kernels, we use TMA Persistent Cooperative kernels with no Ping Pong.

Cluster sizes for all kernels are 1x1x1. I did not see much speedups (if any) from 2x1x1 and keeping 1x1x1 kept the search space manageable

| Size | Best TFLOPS | Speedup | Best Config | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 128³ | 0.40 | 157.5% | 128x128x64, Heuristic, Swizzle=1, Heuristic | 0.14 - 0.40 |

| 256³ | 2.98 | 147.9% | 128x128x64, Heuristic, Swizzle=1, Heuristic | 0.92 - 2.98 |

| 512³ | 20.51 | 127.9% | 128x128x64, Along N, Swizzle=2, DataParallel | 7.12 - 20.51 |

| 1024³ | 126.14 | 98.8% | 128x128x64, Heuristic, Swizzle=2, DataParallel | 11.76 - 126.14 |

| 2048³ | 497.56 | 100.9% | 128x256x64, Along M, Swizzle=4, Heuristic | 71.32 - 497.56 |

| 4096³ | 654.97 | 88.1% | 128x256x64, Along N, Swizzle=8, SplitK | 208.44 - 654.97 |

| 6144³ | 672.66 | 96.5% | 128x256x64, Along N, Swizzle=1, SplitK | 280.22 - 672.66 |

| 8192³ | 599.33 | 90.2% | 128x256x64, Heuristic, Swizzle=8, Heuristic | 312.44 - 599.33 |

Below we can see the breakdowns for different configurations splits:

Raster + Swizzle

Swizzle patterns show size-dependent trade-offs where smaller shapes (128³-512³) don’t benefit much from swizzling while larger matrices (4096³-8192³) benefit from aggressive swizzling paired with directional rasterization (Along M/N) to maximize L2 cache reuse and minimize bank conflicts. The transitions align with compute vs. memory-bound regimes.

Splitting Strategy

DataParallel dominates small-to-medium sizes (128³-1024³) where wave quantization is minimal, while SplitK/StreamK starts performing better for large matrices (4096³-6144³) to improve SM utilization. Seems like Heuristic mode offers competitive performance across all sizes by adaptively selecting between strategies so manual tuning seems to be not needed upto a fairly competitive performance.

Across all configs

Here’s all the results combined!

Results in detail

The visualization below allows you to explore these configurations in detail. Select a matrix size to view the top 10 performing configurations for each size combinations.

Final Thoughts

We covered a lot in this post but I tried to keep this a shorter than the previous post. We discussed variety of special architectural features that were introduced in Hopper. Blackwell generation GPUs built on these fundamental features. Overall, I was a bit time constraint so it took me a while to put this together. Hopefully, I will get to some fp8/fp4 kernels next on Hopper/Blackwell but for now this will do! I have compiled a bunch of resources below that I found useful. You can almost consider this post to be a survey of a lot of techniques spread across various blogs and articles for Hopper GPUs.

Resources

- Outperforming cuBLAS on H100: a Worklog

- CUTLASS 3.x: Orthogonal, Reusable, and Composable Abstractions for GEMM Kernel Design

- Developing Optimal CUDA Kernels on Hopper Tensor Cores

- CUDA Techniques to Maximize Compute and Instruction Throughput

- NVIDIA Hopper Architecture In-Depth

- CUTLASS Tutorial: Persistent Kernels and Stream-K

- Efficient GEMM in CUDA

- CUDA C++ Programming Guide: Spatial Partitioning (Warp Specialization)

- Warp Specialization Blog Post

- Deep Dive on CUTLASS Ping-Pong GEMM Kernel

- Why we have both Ping-pong and Cooperative schedule?

- Stream-K Paper

- NVIDIA Deep Learning Performance Guide

- bertmaher/simplegemm

- ColfaxResearch/cfx-article-src

- What is PermutationMNK in TiledMMA in CUTLASS 3.4 changes? Swizzles and their usage in CuTeDSL Kernels CuTe Swizzle

- PTX Docs