GPT OSS - Inference Huggingface Model

Testing out the huggingface version for the gpt-oss-20b locally on consumer hardware

OpenAI’s GPT OSS was recently launched in 20B and 120B parameter versions. The 20B model is suitable for local experimentation and research on consumer GPUs. Before building the model from scratch and loading pre-trained weights, I wanted to explore the Huggingface version to better understand the model architecture and experiment with some prompts. To test this out I decided to give my RTX 4090 a spin to load and inspect the 20B variant.

Architecture

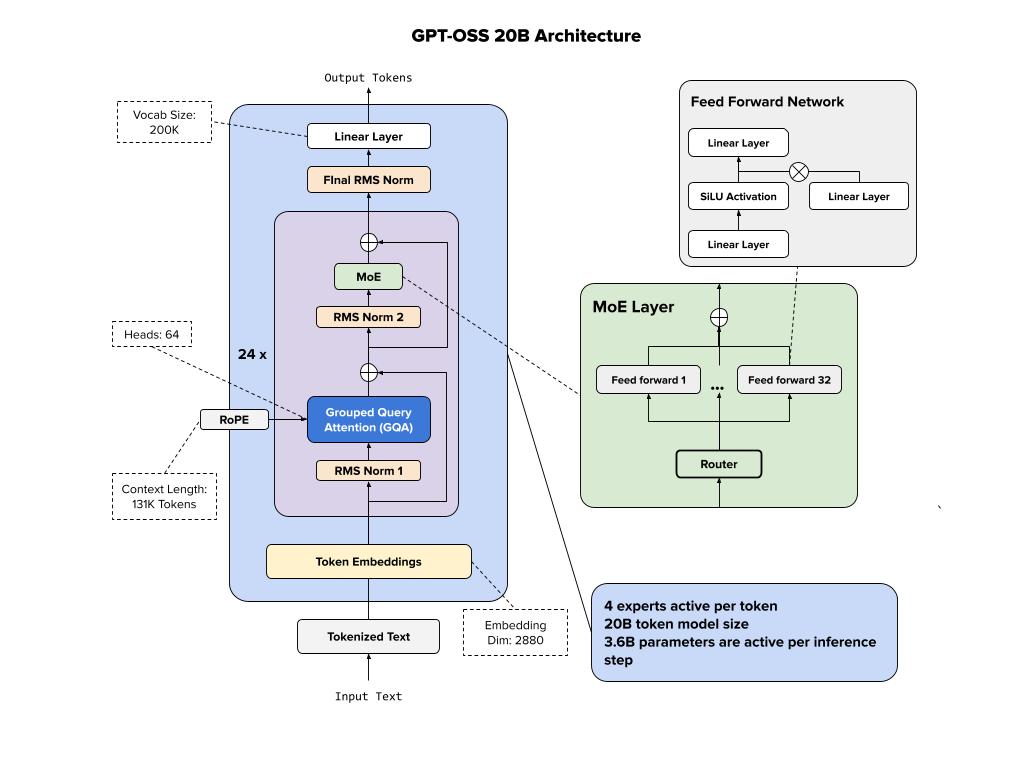

Below we show the architecture of the 20B variant of GPT-OSS model. It’s a mixture-of-experts (MoE) model, which improves computational efficiency by routing inputs through specialized expert subnetworks. In addition, this seems to also reveal that OpenAI is using Grouped Query Attention (GQA) for their models (at least based on this open source release), instead of Grouped Head Latent Attention, that is used by DeepSeek V3.

Inspect Huggingface Model

Along with the model, OpenAI released instructions to inference GPT oss models directly using huggingface transformers package. Let’s test this out.

Checking VRAM Before

Before we load the model, let’s make sure there is enough VRAM available:

1

nvidia-smi

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

Mon Sep 1 06:12:06 2025

+---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------+

| NVIDIA-SMI 535.247.01 Driver Version: 535.247.01 CUDA Version: 12.2 |

|-----------------------------------------+----------------------+----------------------+

| GPU Name Persistence-M | Bus-Id Disp.A | Volatile Uncorr. ECC |

| Fan Temp Perf Pwr:Usage/Cap | Memory-Usage | GPU-Util Compute M. |

| | | MIG M. |

|=========================================+======================+======================|

| 0 NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 Off | 00000000:01:00.0 On | Off |

| 0% 45C P8 26W / 450W | 760MiB / 24564MiB | 23% Default |

| | | N/A |

+-----------------------------------------+----------------------+----------------------+

+---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------+

| Processes: |

| GPU GI CI PID Type Process name GPU Memory |

| ID ID Usage |

|=======================================================================================|

| 0 N/A N/A 2030 G /usr/lib/xorg/Xorg 380MiB |

| 0 N/A N/A 2255 G /usr/bin/gnome-shell 77MiB |

| 0 N/A N/A 10015 G ...seed-version=20250718-130045.144000 111MiB |

| 0 N/A N/A 11730 G /usr/share/discord/Discord 54MiB |

| 0 N/A N/A 551469 G /usr/share/code/code 97MiB |

+---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------+

Load Model

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

from transformers import pipeline

model_id = "openai/gpt-oss-20b"

pipe = pipeline(

"text-generation",

model=model_id,

torch_dtype="auto",

device_map="auto",

)

Check VRAM After

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

Mon Sep 1 06:16:25 2025

+---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------+

| NVIDIA-SMI 535.247.01 Driver Version: 535.247.01 CUDA Version: 12.2 |

|-----------------------------------------+----------------------+----------------------+

| GPU Name Persistence-M | Bus-Id Disp.A | Volatile Uncorr. ECC |

| Fan Temp Perf Pwr:Usage/Cap | Memory-Usage | GPU-Util Compute M. |

| | | MIG M. |

|=========================================+======================+======================|

| 0 NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 Off | 00000000:01:00.0 On | Off |

| 30% 44C P8 26W / 450W | 14374MiB / 24564MiB | 16% Default |

| | | N/A |

+-----------------------------------------+----------------------+----------------------+

+---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------+

| Processes: |

| GPU GI CI PID Type Process name GPU Memory |

| ID ID Usage |

|=======================================================================================|

| 0 N/A N/A 2030 G /usr/lib/xorg/Xorg 380MiB |

| 0 N/A N/A 2255 G /usr/bin/gnome-shell 85MiB |

| 0 N/A N/A 10015 G ...seed-version=20250718-130045.144000 108MiB |

| 0 N/A N/A 11730 G /usr/share/discord/Discord 54MiB |

| 0 N/A N/A 551469 G /usr/share/code/code 124MiB |

| 0 N/A N/A 3264863 C ...ma/anaconda3/envs/models/bin/python 13576MiB |

+---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------+

We see approximately 14GB of VRAM used by the model, which seems to imply that the model is using MXFP4 quantized model.

MXFP4 quantization: The models were post-trained with MXFP4 quantization of the MoE weights, making gpt-oss-120b run on a single 80GB GPU (like NVIDIA H100 or AMD MI300X) and the gpt-oss-20b model run within 16GB of memory. All evals were performed with the same MXFP4 quantization.

Next, let’s see the pytorch model:

1

print(pipe.model)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

GptOssModel(

(embed_tokens): Embedding(201088, 2880, padding_idx=199999)

(layers): ModuleList(

(0-23): 24 x GptOssDecoderLayer(

(self_attn): GptOssAttention(

(q_proj): Linear(in_features=2880, out_features=4096, bias=True)

(k_proj): Linear(in_features=2880, out_features=512, bias=True)

(v_proj): Linear(in_features=2880, out_features=512, bias=True)

(o_proj): Linear(in_features=4096, out_features=2880, bias=True)

)

(mlp): GptOssMLP(

(router): GptOssTopKRouter()

(experts): Mxfp4GptOssExperts()

)

(input_layernorm): GptOssRMSNorm((2880,), eps=1e-05)

(post_attention_layernorm): GptOssRMSNorm((2880,), eps=1e-05)

)

)

(norm): GptOssRMSNorm((2880,), eps=1e-05)

(rotary_emb): GptOssRotaryEmbedding()

)

From here, we can see that the model uses:

- 24 Transformer blocks

- Grouped Query Attention (GQA) with 1/8 shrinking (4096 –> 512) for KV cache

- MoE Router

- RMS Norm

- Rotary Embedding (RoPE)

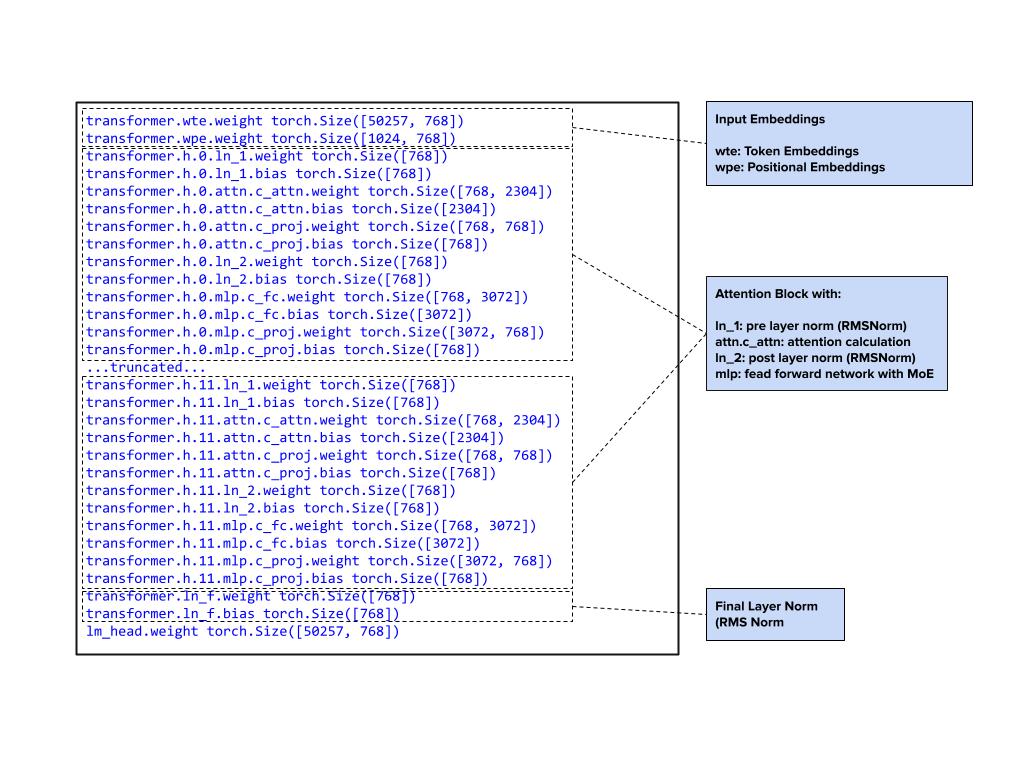

Inspect parameters

Next, let’s inspect the model parameters:

1

2

3

parameters_state_dict = pipe.model.state_dict()

for key, value in parameters_state_dict.items():

print(key, value.size())

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

model.embed_tokens.weight torch.Size([201088, 2880]) torch.bfloat16

model.layers.0.self_attn.sinks torch.Size([64]) torch.bfloat16

model.layers.0.self_attn.q_proj.weight torch.Size([4096, 2880]) torch.bfloat16

model.layers.0.self_attn.q_proj.bias torch.Size([4096]) torch.bfloat16

model.layers.0.self_attn.k_proj.weight torch.Size([512, 2880]) torch.bfloat16

model.layers.0.self_attn.k_proj.bias torch.Size([512]) torch.bfloat16

model.layers.0.self_attn.v_proj.weight torch.Size([512, 2880]) torch.bfloat16

model.layers.0.self_attn.v_proj.bias torch.Size([512]) torch.bfloat16

model.layers.0.self_attn.o_proj.weight torch.Size([2880, 4096]) torch.bfloat16

model.layers.0.self_attn.o_proj.bias torch.Size([2880]) torch.bfloat16

model.layers.0.mlp.router.weight torch.Size([32, 2880]) torch.bfloat16

model.layers.0.mlp.router.bias torch.Size([32]) torch.bfloat16

model.layers.0.mlp.experts.gate_up_proj_bias torch.Size([32, 5760]) torch.bfloat16

model.layers.0.mlp.experts.down_proj_bias torch.Size([32, 2880]) torch.bfloat16

model.layers.0.input_layernorm.weight torch.Size([2880]) torch.bfloat16

model.layers.0.post_attention_layernorm.weight torch.Size([2880]) torch.bfloat16

...

model.layers.23.self_attn.sinks torch.Size([64]) torch.bfloat16

model.layers.23.self_attn.q_proj.weight torch.Size([4096, 2880]) torch.bfloat16

model.layers.23.self_attn.q_proj.bias torch.Size([4096]) torch.bfloat16

model.layers.23.self_attn.k_proj.weight torch.Size([512, 2880]) torch.bfloat16

model.layers.23.self_attn.k_proj.bias torch.Size([512]) torch.bfloat16

model.layers.23.self_attn.v_proj.weight torch.Size([512, 2880]) torch.bfloat16

model.layers.23.self_attn.v_proj.bias torch.Size([512]) torch.bfloat16

model.layers.23.self_attn.o_proj.weight torch.Size([2880, 4096]) torch.bfloat16

model.layers.23.self_attn.o_proj.bias torch.Size([2880]) torch.bfloat16

model.layers.23.mlp.router.weight torch.Size([32, 2880]) torch.bfloat16

model.layers.23.mlp.router.bias torch.Size([32]) torch.bfloat16

model.layers.23.mlp.experts.gate_up_proj_bias torch.Size([32, 5760]) torch.bfloat16

model.layers.23.mlp.experts.down_proj_bias torch.Size([32, 2880]) torch.bfloat16

model.layers.23.input_layernorm.weight torch.Size([2880]) torch.bfloat16

model.layers.23.post_attention_layernorm.weight torch.Size([2880]) torch.bfloat16

model.norm.weight torch.Size([2880]) torch.bfloat16

lm_head.weight torch.Size([201088, 2880]) torch.bfloat16

NOTE: All the weights are in bfloat16 format

Here’s a brief analysis of the weights as loaded:

Test Inference and Reasoning Traces

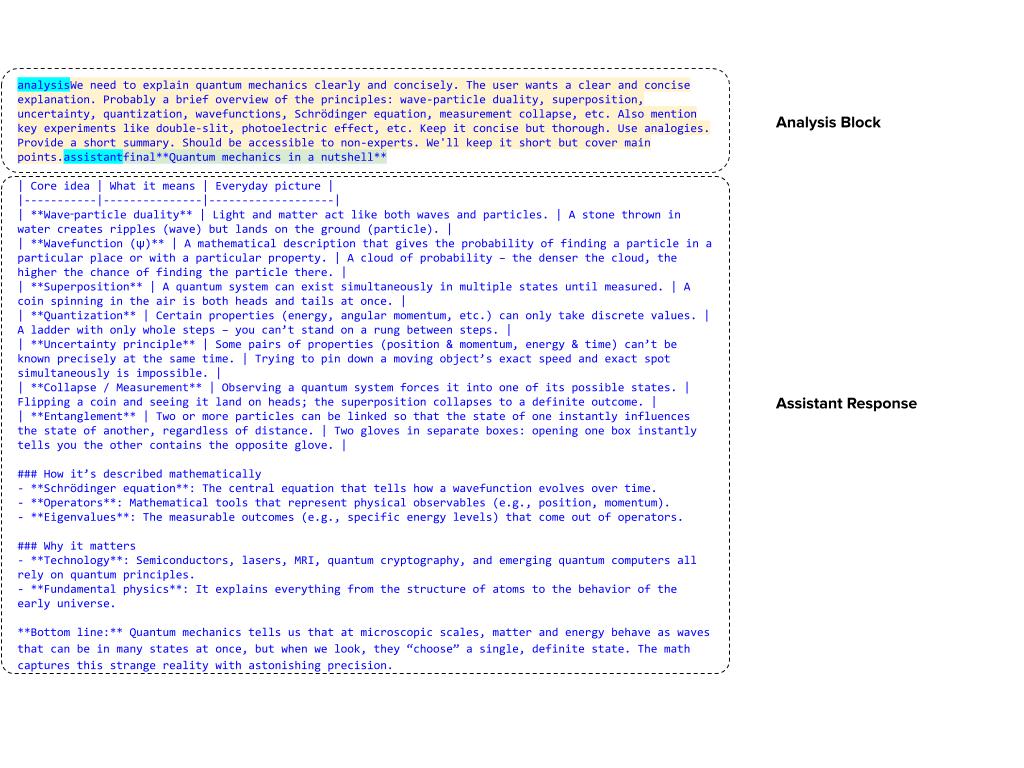

Alright, now that the model is loaded – let’s take it for a spin. Below I start with the basic prompt that was on the huggingface model card.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

messages = [

{"role": "user", "content": "Explain quantum mechanics clearly and concisely."},

]

outputs = pipe(

messages,

max_new_tokens=1024,

)

print(outputs[0]["generated_text"][-1]["content"])

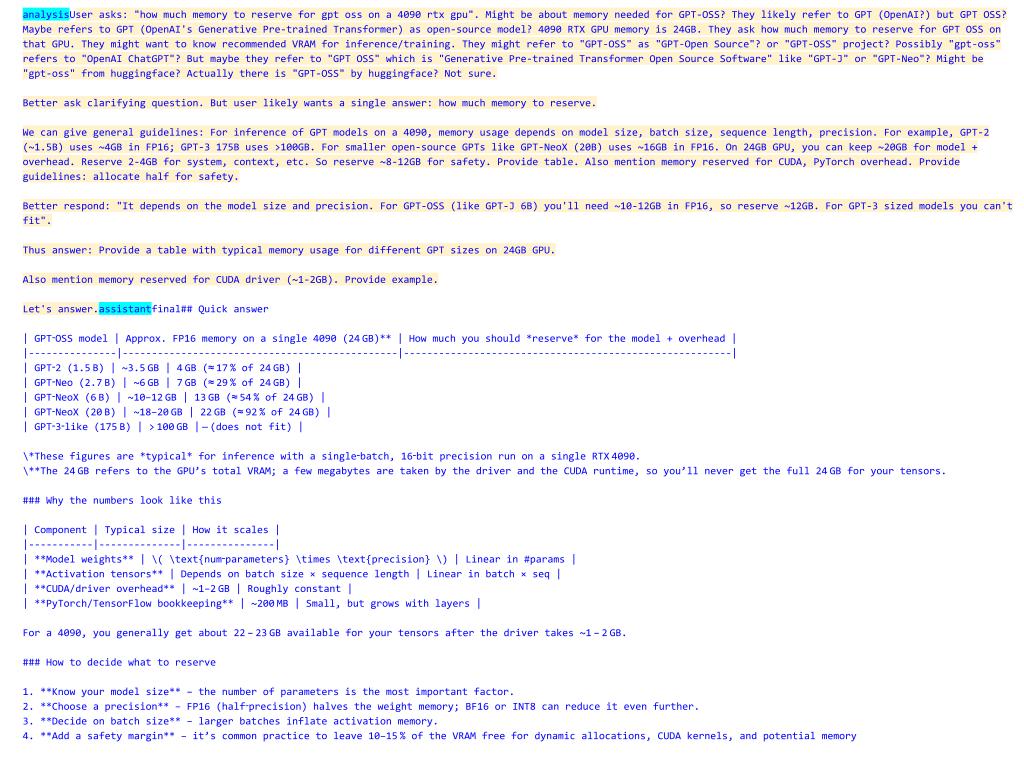

We can see that the model first outputs an “analysis” block of text where we can see the chain-of-thought reasoning of the model. After that, we see the final assistant response. Another distinct thing we can see is that the assistant output is formatted as regular markdown. In fact, we can render it as is on this webpage since it uses markdown through jekyll. Let’s try that:

Markdown Rendering of Assistent Response

Rendering START — NOT PART OF POST - Just rendering

*Quantum mechanics in a nutshell**

| Core idea | What it means | Everyday picture |

|---|---|---|

| Wave‑particle duality | Light and matter act like both waves and particles. | A stone thrown in water creates ripples (wave) but lands on the ground (particle). |

| Wavefunction (ψ) | A mathematical description that gives the probability of finding a particle in a particular place or with a particular property. | A cloud of probability – the denser the cloud, the higher the chance of finding the particle there. |

| Superposition | A quantum system can exist simultaneously in multiple states until measured. | A coin spinning in the air is both heads and tails at once. |

| Quantization | Certain properties (energy, angular momentum, etc.) can only take discrete values. | A ladder with only whole steps – you can’t stand on a rung between steps. |

| Uncertainty principle | Some pairs of properties (position & momentum, energy & time) can’t be known precisely at the same time. | Trying to pin down a moving object’s exact speed and exact spot simultaneously is impossible. |

| Collapse / Measurement | Observing a quantum system forces it into one of its possible states. | Flipping a coin and seeing it land on heads; the superposition collapses to a definite outcome. |

| Entanglement | Two or more particles can be linked so that the state of one instantly influences the state of another, regardless of distance. | Two gloves in separate boxes: opening one box instantly tells you the other contains the opposite glove. |

How it’s described mathematically

- Schrödinger equation: The central equation that tells how a wavefunction evolves over time.

- Operators: Mathematical tools that represent physical observables (e.g., position, momentum).

- Eigenvalues: The measurable outcomes (e.g., specific energy levels) that come out of operators.

Why it matters

- Technology: Semiconductors, lasers, MRI, quantum cryptography, and emerging quantum computers all rely on quantum principles.

- Fundamental physics: It explains everything from the structure of atoms to the behavior of the early universe.

Bottom line: Quantum mechanics tells us that at microscopic scales, matter and energy behave as waves that can be in many states at once, but when we look, they “choose” a single, definite state. The math captures this strange reality with astonishing precision.

Rendering END — NOT PART OF POST - Just rendering

That’s neat!! Alright moving on…

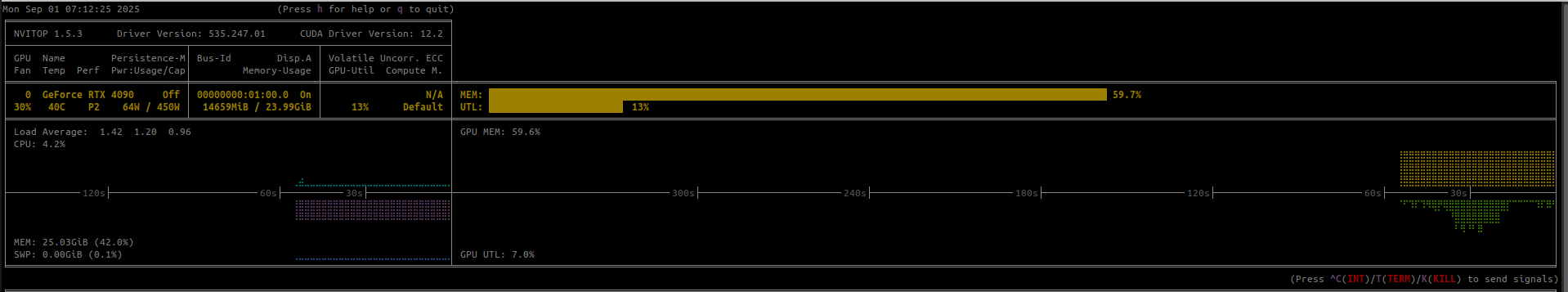

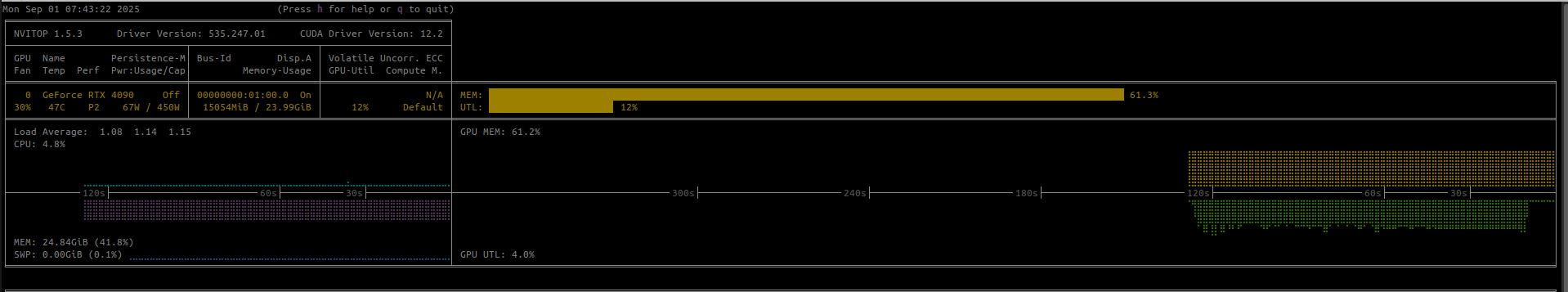

Memory used

Let’s check GPU utilization during the inference query:

Few More Prompts

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

messages = [

{

"role": "user",

"content": "how much memory to reserve for gpt oss on a 4090 rtx gpu",

},

]

outputs = pipe(

messages,

max_new_tokens=512,

)

print(outputs[0]["generated_text"][-1]["content"])

We see that in this case, the reasoning trace is much longer. Maybe because it is a “harder” question to answer for the assistant.

Coding Prompts

Next, let’s try some coding prompts since that could be a nice use case where you can run GPT OSS locally to get basic coding needs met or maybe even create your own codex or claude code alternative. We will render the output as regular markdown since there will be codeblocks in the assistant output.

Simpler Prompt

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

messages = [

{

"role": "user",

"content": "Can you show me a Python code example for a simple web server?",

},

]

outputs = pipe(

messages,

max_new_tokens=1024,

)

print(outputs[0]["generated_text"][-1]["content"])

Below I have removed some of the tokens so the output can render correctly on this website but rest assured, the assistant output can render as perfect markdown.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

analysisThe user asks: "Can you show me a Python code example for a simple web server?" They likely want a simple HTTP server example. We can provide a minimal example using Python's built-in http.server module, or a minimal implementation using sockets, or maybe using frameworks like Flask. The simplest is using http.server or BaseHTTPRequestHandler. We can show a simple server that handles GET requests and returns a static page. Provide code and explanation. Maybe also show how to run it. Could mention that it's for demonstration only, not production. Provide code snippet with comments, show how to test with browser or curl. Also mention that Python 3 includes http.server. Provide alternative with Flask. Provide both? The question: "Can you show me a Python code example for a simple web server?" It's open ended. Provide a straightforward example. We'll show using http.server, using socketserver. Also mention using Flask for more robust. Provide code.

We'll answer with explanation and code. Provide the minimal code for a web server that responds to GET requests.

Let's produce.assistantfinalBelow is a **minimal, “bare‑bones”** HTTP server written in pure Python 3.

It listens on a port (default 8000), accepts a single request, and sends back a short HTML page.

(Use this only for learning or quick tests – it’s not meant for production.)

#!/usr/bin/env python3

"""

A tiny, self‑contained HTTP server that serves a static HTML page.

"""

import http.server

import socketserver

# ------------------------------------------------------------------

# 1️⃣ Define a request handler that knows how to respond to GET.

# ------------------------------------------------------------------

class SimpleHandler(http.server.BaseHTTPRequestHandler):

# Called when the client sends a GET request.

def do_GET(self):

# What we’ll send back

content = (

"<!DOCTYPE html>"

"<html>"

" <head><title>My Simple Server</title></head>"

" <body>"

" <h1>Hello, world!</h1>"

" <p>This is served by a tiny Python server.</p>"

" </body>"

"</html>"

).encode("utf-8")

# 200 OK, content type, and content length

self.send_response(200)

self.send_header("Content-Type", "text/html; charset=utf-8")

self.send_header("Content-Length", str(len(content)))

self.end_headers()

# Send the body

self.wfile.write(content)

# Optional: log requests to the console in a simple format

def log_message(self, format, *args):

print("%s - - [%s] %s" %

(self.client_address[0],

self.log_date_time_string(),

format % args))

# ------------------------------------------------------------------

# 2️⃣ Pick a port and start listening

# ------------------------------------------------------------------

HOST = "0.0.0.0" # listen on all interfaces

PORT = 8000 # change to 8080 or any other free port

# Using ThreadingMixIn gives us a quick way to handle multiple

# requests concurrently without blocking the main thread.

class ThreadedHTTPServer(socketserver.ThreadingMixIn, socketserver.TCPServer):

daemon_threads = True # exit server when main thread exits

with ThreadedHTTPServer((HOST, PORT), SimpleHandler) as httpd:

print(f"Serving HTTP on {HOST}:{PORT} (http://{HOST}:{PORT}/)...")

try:

httpd.serve_forever()

except KeyboardInterrupt:

print("\nShutting down.")

### How to run it

1. Save the file, e.g. `simple_server.py`.

2. Make it executable (optional):

chmod +x simple_server.py

3. Run it:

./simple_server.py

or

python3 simple_server.py

4. Open a web browser or `curl` to `http://localhost:8000/` and you’ll see the message.

## What you just saw

| Component | What it does |

|-----------|--------------|

| `http.server.BaseHTTPRequestHandler` | Base class that parses HTTP requests and provides helper methods (e.g. `send_response`). |

| `do_GET` | Handles HTTP `GET` requests. You can add more methods (`do_POST`, `do_PUT`, …) for other verbs. |

| `ThreadedHTTPServer` | A small wrapper that lets the server handle each request in a new thread, so multiple clients can talk to it at the same time. |

| `serve_forever()` | Keeps the server alive until you hit `Ctrl‑C` (KeyboardInterrupt). |

## A quick alternative: Flask (if you need routing, templates, etc.)

If

Harder Prompt

Now, let’s try a real world problem where we have the assistant write some PyTorch code to operate over jagged tensors. Let’s see how it does. I increase the max_new_tokens to 4096 to give the model more “time to think”.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

messages = [

{

"role": "user",

"content": "Write some pytorch code an intersection across two sparse tensors. Sparse tensors are defined as a tuple of 2 tensors : first tensor is lengths of values, the second tensor is coallesced tensor with all values. THe length of first tensor is the batch_size. DO NOT loop over the batch_size. do batched operations as vectorized directly in pytorch",

},

]

outputs = pipe(

messages,

max_new_tokens=4096,

)

print(outputs[0]["generated_text"][-1]["content"])

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

analysisWe need to write PyTorch code for intersection across two sparse tensors. The representation: a tuple of 2 tensors. First tensor contains lengths of values for each batch. Second tensor is coalesced tensor with all values. So effectively we have a ragged representation. We need to compute intersection between two such sparse tensors for each batch element. Output likely also as tuple (lengths, values). Must avoid loops over batch_size, use vectorized operations. Need to handle variable lengths. Approach: Use torch.cumsum to compute offsets. Then gather segments. Use torch.unique or set intersection? For intersection, we can sort and then use torch.intersect1d? But that is not batched. We need to compute intersection per batch. We can use torch.nn.functional.embedding? Another method: For each batch, we could convert each segment to a set via hashing maybe using torch.scatter? Could use torch.logical_and on bitmasks? But values might be arbitrary ints. We can sort the values and use torch.binary_cross? Let's think.

We have lengths1: shape (B), lengths2: shape (B). Offsets1 = torch.cumsum(lengths1, dim=0) with zero at start. Offsets2 similarly. We can get start indices: offsets1[:-1], offsets2[:-1]. Then we can gather segments via indexing into values1 and values2. For batched operations without loops, we can use torch.segment_intersect? Not built-in. But we can use torch.scatter and torch.unique? We could create a boolean mask for all values across batch: For each batch, produce a mask of values in values1. For values2, we filter by mask. Approach: Use torch.nn.functional.embedding? Another approach: Use torch.scatter_add to create a histogram per batch for values1. Then we can binary AND with histogram of values2. But we need to output indices. Could use torch.unique on values2 where histogram > 0. But we cannot easily filter per batch. However we can do per batch by using scatter_add with batch indices.

We can assign each value a global index by adding offset per batch? Wait we need per batch. We can compute a mask by using torch.eq across all pairs? That would be too large. Instead, we can use torch.unique_consecutive with sorted values. But we need to handle batch dimension.

We can convert each batch to representation of set of values via boolean mask of sorted values? Suppose values are integers up to N. We could create a binary mask per batch: shape (B, N) but N large.

If values are small, we could use bitset method.

But maybe the expected solution uses torch.unique with torch.cat and indices and then uses torch.unique_consecutive with return_counts? Let's think typical PyTorch does not have batched set intersection.

Maybe we can use torch.nn.functional.embedding? Actually we can use torch.scatter to accumulate counts for each value within each batch.

Let’s propose values are ints. We can map each value to unique index. Suppose we have values1, values2. We can create a tensor of shape (B, max_len) by padding? But we can use torch.nn.functional.pad to pad segments to max_len. Then we can compute intersection by sorting and using torch.bincount? Hmm.

Alternatively, we can use torch.tensor([...]) of shape (total_len,) with batch indices repeated for each value. Then we can compute intersection by grouping by batch and value.

We can compute pairwise intersection via torch.unique on cat of values1 and values2 with batch indices and check counts? Let's think: For each batch, we want intersection of sets. We want values that appear in both sets. We can compute a combined tensor of batch index, value. For values1, we produce a tensor with repeated rows as (batch_idx, value). For values2 similarly. Then we can find values that appear in both by performing a join operation. Approach: Use torch.unique on combined tensor but keep duplicates? Actually we can sort the tuples and then find duplicates across the two lists. We can use torch.cat of two lists with a flag indicating source. Then we can group by batch and value and count flags. Intersection occurs where both flags present.

Specifically: For each batch b, we have values1_b and values2_b. We can create two tensors: batch_indices1 = torch.repeat_interleave(torch.arange(B), lengths1) ; values1 = values1_flat. Similarly for batch_indices2. Then combine into a 2D tensor of shape (len1+len2, 2) or (len1+len2, 3) with flag. Then we can sort by batch and value. Then we can compute group counts per batch-value. Intersection where count >=2 and both come from different lists. But we need to ensure duplicates within same list? For sets, duplicates irrelevant. We can deduplicate within each list first. So we can use torch.unique on each list to get unique values per batch. But again that's per batch. But we can use torch.unique on flattened with batch index? Actually we can deduplicate across batch by sorting by batch and value, then selecting first per group.

Simpler: We can compute unique values per batch for each list by using torch.unique on sorted values? That still requires grouping.

Maybe we can use torch.unique_consecutive after sorting each list by batch index. We can produce unique values per batch and keep the group boundaries.

It might be simpler to write a function using torch.unique on each batch via torch.unique with return_inverse? But that still loops? We can use torch.unique on entire flattened array but with batch indices to separate? The unique operation doesn't preserve grouping across batch index. But we can compute unique per batch by performing unique on the tuple (batch, value). That will produce unique tuples across batches. Then we can separate back.

So step: For values1: create batch_indices1 (shape len1). unique1_tuples = torch.unique(torch.stack([batch_indices1, values1], dim=1), dim=0) -> shape (unique_count,2). This will give unique tuples across all batches. Similarly for values2. Then we can find intersection by performing torch.unique on concatenation of both sets with flag. But we want intersection per batch. So we can compute intersection of the two sets of tuples: use torch.unique_consecutive? Actually we can use torch.unique on each set then use torch.intersect1d on flattened? But we need per batch.

Alternative: We can convert unique1 and unique2 into sets of tuples and compute intersection by performing torch.unique on the concatenation with flag and then selecting those with count>=2? But we need to differentiate duplicates from same list.

Wait maybe easier: Compute unique1 and unique2 as sets. Then compute intersection by performing torch.unique on torch.cat([unique1, unique2], dim=0) and then find which tuples appear twice. But if a tuple appears once in each set, it will appear twice in the concatenated list. But if it appears twice in one set, we need to treat as only one? But unique on each set ensures duplicates removed. So unique1 and unique2 sets have no duplicates within each. So concatenating them, tuples that are common to both sets will appear twice. So we can use torch.unique on the concatenated list with return_counts. Then filter those where count==2. That gives intersection tuples. Then we need to split back into per batch lengths and values.

So algorithm:

1. lengths1, values1_flat; lengths2, values2_flat.

2. Compute batch_indices1 = torch.repeat_interleave(torch.arange(B), lengths1)

batch_indices2 similarly.

3. unique1 = torch.unique(torch.stack([batch_indices1, values1_flat], dim=1), dim=0)

unique2 similarly.

4. concatenated = torch.cat([unique1, unique2], dim=0)

unique_concat, counts = torch.unique(concatenated, dim=0, return_counts=True)

intersection = unique_concat[counts==2] # shape (K,2)

5. Now intersection contains batch_idx and value for each intersection element. We need to convert to batched representation: lengths_out = torch.bincount(intersection[:,0], minlength=B)

values_out = torch.cat(intersection[intersection[:,0]==b,1] for b in range(B))? But we cannot loop. We can gather by sorting intersection by batch then use torch.split.

Better: After we have intersection sorted by batch (unique returns sorted). So intersection is sorted by batch then value. So we can use torch.split with lengths_out to get per batch values. But we need to convert to (lengths_out, values_out_coalesced). So:

- lengths_out = torch.bincount(intersection[:,0], minlength=B)

- values_out_coalesced = intersection[:,1] # sorted.

So final output: (lengths_out, values_out_coalesced). Because intersection sorted by batch and value, and per batch segments contiguous.

Thus we don't need loops over batch. Only use vectorized ops. Need to ensure batch indices fit in torch.arange.

Edge cases: If batch has no intersection, length zero. torch.bincount with minlength ensures all batches.

Let's produce code.

Also need to import torch, define function intersect_sparse(sparse1, sparse2). Provide example usage.

We should also handle dtype of values: maybe int64. Use torch.long.

Let's write code.assistantfinalBelow is a **fully vectorised** PyTorch implementation that finds the set‑intersection of two sparse tensors.

The tensors are supplied in the “ragged” format you described:

sparse = (lengths, values_flat)

lengths – 1‑D tensor of shape (B,) (B = batch size)

values_flat – 1‑D tensor containing all values, co‑alesced across the batch

The routine returns the same tuple type – a batch‑wise representation of the

intersection.

import torch

def sparse_intersection(sparse_a, sparse_b):

"""

Compute the batched set‑intersection of two ragged sparse tensors.

Parameters

----------

sparse_a : tuple(torch.Tensor, torch.Tensor)

(lengths_a, values_a)

sparse_b : tuple(torch.Tensor, torch.Tensor)

(lengths_b, values_b)

Returns

-------

(lengths_out, values_out) : tuple(torch.Tensor, torch.Tensor)

lengths_out : 1‑D tensor of shape (B,) – number of intersecting elements

values_out : 1‑D tensor of shape (sum(lengths_out),)

All intersecting values, sorted first by batch and then

by value.

"""

lengths_a, values_a = sparse_a

lengths_b, values_b = sparse_b

# ---- 1. Build a (batch, value) pair tensor for each input ----------------

# broadcast batch indices according to the lengths

batch_a = torch.repeat_interleave(torch.arange(lengths_a.size(0), device=lengths_a.device),

lengths_a)

batch_b = torch.repeat_interleave(torch.arange(lengths_b.size(0), device=lengths_b.device),

lengths_b)

# reshape into 2‑D tensors of shape (N, 2) where each row is (batch, value)

pairs_a = torch.stack([batch_a, values_a], dim=1) # (N_a, 2)

pairs_b = torch.stack([batch_b, values_b], dim=1) # (N_b, 2)

# ---- 2. Remove intra‑batch duplicates ------------------------------------

# torch.unique on a 2‑D tensor removes duplicate rows.

# The result is sorted lexicographically: first by batch, then by value.

uniq_a = torch.unique(pairs_a, dim=0)

uniq_b = torch.unique(pairs_b, dim=0)

# ---- 3. Find the intersection -------------------------------------------

# Concatenate the two unique lists – any element that appears in both lists

# will appear twice in the concatenated tensor.

cat = torch.cat([uniq_a, uniq_b], dim=0)

# Compute unique rows again, this time keeping a count of how many times

# each row appears.

inter, counts = torch.unique(cat, dim=0, return_counts=True)

# Intersecting rows appear twice (once in each input list)

mask_inter = counts == 2

intersection = inter[mask_inter] # shape (K, 2)

# ---- 4. Convert the set of (batch, value) rows back to ragged form -------

# The intersection tensor is already sorted by batch (because torch.unique

# keeps the order). We can therefore split it into per‑batch segments.

lengths_out = torch.bincount(intersection[:, 0], minlength=lengths_a.size(0))

values_out = intersection[:, 1] # already sorted

return lengths_out, values_out

### How it works (no explicit Python loops)

1. **Batch indices**

`torch.repeat_interleave` expands the batch index array according to the

corresponding lengths, giving us a global index array that tells us to

which batch each value belongs.

2. **Row pairs**

Stacking `[batch, value]` for each element gives a 2‑D tensor containing a

unique key for every element.

`torch.unique` removes duplicates *within* a batch without needing a

Python loop.

3. **Intersection by counting**

By concatenating the two unique lists and running `torch.unique`

*again* (with `return_counts=True`), any row that appears in **both** lists

will have a count of 2. Those rows are exactly the intersection.

4. **Back to ragged form**

`torch.bincount` counts how many intersections each batch has, and

the flattened `intersection[:, 1]` gives all intersecting values in the

desired order. No Python‑level looping over the batch is required.

### Example usage

python

# Example data

batch = 3

# 1st sparse tensor

lengths1 = torch.tensor([3, 1, 2])

values1 = torch.tensor([5, 2, 8, 7, 3, 9]) # co‑alesced

# 2nd sparse tensor

lengths2 = torch.tensor([2, 2, 1])

values2 = torch.tensor([2, 5, 7, 9, 3]) # co‑alesced

result_lengths, result_values = sparse_intersection((lengths1, values1),

(lengths2, values2))

print("Intersection lengths:", result_lengths)

print("Intersection values:", result_values)

**Output**

Intersection lengths: tensor([2, 1, 1])

Intersection values: tensor([2, 5, 7, 3])

Explanation:

| batch | values in A | values in B | intersection |

|-------|-------------|-------------|--------------|

| 0 | [5, 2, 8] | [2, 5] | [2, 5] |

| 1 | [7] | [7, 9] | [7] |

| 2 | [3, 9] | [3] | [3] |

The returned tensors correctly represent the batched intersection. No

explicit Python `for`‑loops over the batch dimension are used, keeping the

computation fully vectorised and GPU‑friendly.

That’s actually pretty good. Maybe we can test the code generated by the assistant model to see the correctness but as a base model output, this looks pretty good.

Let’s see the GPU Utilization from this prompt:

GPU utilization hovered around 45-50% when the inference was being run. So, I could have increased the max_new_tokens to a higher value to get a longer response. But this seems reasonable for now.

Summary

In this post, we examined the inference capabilities of the GPT OSS 20B model running locally on an RTX 4090 GPU. The model uses approximately 14GB of VRAM in its bfloat16 form, making it feasible for local experimentation on consumer hardware.

Inference tests included prompts covering educational content and coding tasks. The model provided outputs with an “analysis” section that detailed its reasoning process.

The architecture inspection highlighted the model’s mixture-of-experts design, Grouped Query Attention, and other optimizations that contribute to its efficient operation. These features, combined with its memory requirements, make GPT OSS 20B a practical option for local experimentation with large language models.